Relix Magazine's April/May '06 special on Frank Zappa

This April/May special contained several articles and interviews:

- The Many Minds of Frank Zappa

Pioneer, prankster, musical genius and more – we celebrate the life and times of the one and only Frank Zappa.

Maverick guitar god, stand-up comedy singer, avant-guarde composer and one-size-fits-all provocateur Frank Zappa seemed to emerge a fully formed Grand Wazoo on the Mothers of Invention's 1966 debut, Freak Out! Some 60 albums later, Zappa was just hitting his stride as a "serious" composer when he died of cancer in 1993, a few weeks shy of his 53rd birthday. I believe it's safe to say that his intricately composed jazz-rock, group improvisations, audience participations, frisky electronics, rhythmic conundrums and all manner of spontaneous tomfoolery have influenced the contemporary "jamband" scene no less than the big guy in the black T-shirt. Zappa's music reveals more of its magic with every listen, while his wickedly pertinent satire still sounds as timely, for better or worse, as last night's Daily Show. We hope you enjoy our modest tribute to American music's great cosmic maximalist as much as we enjoyed assembling it. And don't forget to register to vote!

Information is not knowledge /

Knowledge is not wisdom /

Wisdom is not truth /

Truth is not beauty /

Beauty is not love /

Love is not music /

Music is THE BEST ...

–[Packard Goose in] Joe's Garage, Act III

Contents

Vault Allures

Gail Zappa and "Vaultmeister" Joe Travers unlock the door to Frank's buried treasures.

By Richard Gehr

With the Zappa Plays Zappa band about to enter a three-month rehearsal phase prior to a European tour, four recent releases (Joe's Domage, Joe's XMASage, Imaginary Diseases and the Dub Room Special DVD), and a posthumous lifetime achievement award awaiting Frank Zappa at the April 20th Jammy Awards in New York City, things are humming along quite nicely at the Zappa family home near the top of Laurel Canyon in Los Angeles. The compound's business end is crammed with commemorative discs of every precious metal, original album artwork (hey, there's the Uncle Meat sculpture!), and other evocative ephemera. Something in the air suggests significant treats in store for Zappa fans, with the fabled vault finally disgorging its treasures after a long dry spell. His wife, Gail, and official Vaultmeister Joe Travers, who will do double duty as ZPZ's drummer, promise as much, and a longtime fan can only ask:

1) 59 Words from The Real Frank Zappa Book" (1989):

"... [Y]ou may find a little poodle over here, a little blow job over there, etc., etc. I am not obsessed by poodles or blow jobs, however; these words (and others of equal insignificance), along with pictorial images and melodic themes, recur throughout the albums, interviews, films, videos (and this book) for no other reason than to unify the 'collection.'"

What took you so long?

Gail Zappa: There was a ten-year holdback that prevented me from getting into a distribution deal with any recording involving a touring band. Which means we can start releasing a lot of stuff we were unable to release. Until now I could only release it in cooperation with Ryko — but that word does not apply to my relationship with them. We could always put out anything we wanted through mail order, but that's the land of diminishing returns no matter what you do. There are all sorts of considerations the person who would like to consume Frank's unreleased music really doesn't appreciate. Some do, don't get me wrong. But it's expensive to maintain the technology needed to reconstitute what's in the vault, and we had to put the studio back together.

So what's in the vault and when will you let it out?

Gail: We'd never, ever done an inventory of the vault. That inventory existed in Frank's head and it went with him. You could say there's X number of boxes in the vault, but there's no way you can represent what the hell's in them. You can make a cursory evaluation by going through and looking at what kinds of tapes there are. But there's also a lot of visual stuff that had nothing to do with the Ryko deal. And even if you see a box that says, "This contains X," it doesn't necessarily mean that X is in there, or X is complete or X is retrievable from the format it lives in or that we had any way to transfer it at the time. So we've rebuilt the ancient technology and we have our little convection oven ...

Joe Travers: It's not little.

Gail: ... And the prescribed baking formula. How many muffins have you produced, Joe?

Joe: Forty or more reels over the past couple of years. From 1968 to '75, anything recorded on Scotch tape will play; anything on Ampex won't and needs to be baked.

Gail: Apart from boxes labeled with a recording or event, you also have all these boxes filled with "build" reels, where Frank's transferred stuff to make into something else. Or you'll find a box that just has a group of things in it, stuff stacked together that was mixed at a particular time. Every variation you can think of, we find. Question is, how do we put them together and respect Frank's intentions?

2) "Once upon a time, somebody say to me, what is your conceptual continuity? Well, I told 'em right then, it should be easy to see, the crux of the biscuit is the apostrophe." —Fido (an unmodified dog), "Stink-Foot," Apostrophe (') (1974)

Frank repeatedly had several albums ready for release when he died. What's their status today?

Joe: We released Civilization Phaze III in 1994 and Ryko released Frank's Have I Offended Someone? best-of in 1997. That leaves Trance-Fusion, Dance Me This and The Rage and the Fury waiting to see the light of day, Trance-Fusion is a guitar record like Shut Up 'n' Play Yer Guitar. The solos are culled from the '84 and '88 tours, with a couple more thrown in. Dance Me This is a Synclavier record like Jazz From Hell. And The Rage and the Fury was the Edgard Varѐse project that happened in the summer of '93 with the Ensemble Modern.

Gail: I decided that when the ten-year hold-back period was up, we'd just start putting things out. By that point we had some info about what the vault contained, and we've divided it up into three basic food groups. Category A consists of mixes Frank actually completed, although there's a lot of variation and leeway. We'll release Category A stuff you've never heard before, that was produced and mixed by Franks on Zappa Records. There's at least one concert project no one knows about that we want to put out on Zappa, too.

Category B would be tapes Frank made, such as all the concert material. Quite a lot of that has either been plucked through for the You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore series and other projects, or was set aside by Frank for something in Category A. So what remains in Category B has the best audio quality and potential as a whole project. And Category C is everything else.

The idea was that the Vaulternative label would be the real deal, the stuff that lives in the vault. We'll release whole concerts on Vaulternative, but we like to keep that pretty quiet. You might ask why. The answer is that once we announce it in advance – and this is the un-fun part – we're deluged with bootlegs. Zappa fans are seriously dedicated, but the people who want to mess it up for everybody else are pretty serious, too.

Do you have a release schedule?

Gail: No, and this is what we're trying to work out. Joe and I have differences of opinion, but there's stuff we can announce, like the Roxy And Elsewhere DVD, which we know no bootlegger has. But Trance-Fusion should be the next Zappa Records release after Imaginary Diseases.

The two concerts seen in the Dub Room Special DVD exist separately on video, and we're working on releasing one of them in surround sound. This also represents our first foray into another project I'm interested in, which is inviting certain well-known producers and engineers who never had an opportunity to work with Frank, but were well aware of, inspired by or interested in his work, to get their hands on a Frank Zappa project. In this regard, we turned over the 1974 KCET concert to Frank Filipetti. And we'll still release the Token of His Extreme DVD by the same band.

Do you feel like time is on your side? Is there any urgency about keeping the brand alive, in getting more of Frank's nusic out there?

Gail: Time is on my side in this regard: There's no way we can get everything out there. We're in a position to release a project a month for five years. We have the content but we don't have the budget. And the only way we can begin to do that is if the audience wakes up and finds itself. So my intention is to announce that the ten-year holdback is over, even if you didn't know it existed, and that Frank Zappa is alive and well.

3) See: The back cover of Absolutely Free (1967) features an ad for FYDO-brand dog collars ("fits well!"); the "here Fido!" arrival of Frunobulax, the mutant poodle of "Cheepnis"

(Roxy and Elsewhere, 1974); Phydeaux III, Zappa's tourbus in the late '70s.

Why don't you do something along the lines of the Grateful Dead's Dick's Picks?

Gail: The Joe's Corsage series is our answer to that question* Those are official releases consisting of something extra and have nothing to do with our main agenda with respect to the vault. Which doesn't mean we don't work on them. Of course we do. The closest thing you might relate the Corsage series to is The Mystery Disc. We're just sharing nuggets we find in the vault and can't do anything else with. Let me tell you how the series originated: We had to do something for Mother's Day 2004 because it suddenly occurred to us that we were coming up to the 40th anniversary of the original Mother's Day, which was May 10, 1964. when Frank named the band. So we put out Joe's Corsage in June.

Joe: It was only about a half-hour's worth of material.

Gail: I fell in love with the album and wanted to do more of this kind of thing. Then I thought, "What the hell, we can do whatever we want, whenever we want." It's "anything anytime anywhere for no reason at all." The titles play on Joe's Garage, of course. And the fact of the matter is that Joe's Garage has everything you'll ever need to know about anything in terms of how society and civilization actually works. It's all there. I can find a Corsage that expands upon any point of Joe's Garage. It's all homeomorphic.

Our main job is to put out what he wanted to put out I have to protect the intent of the Composer and the integrity of his Work. Most of the time it's pretty straightforward. Some times we know what to do simply by hearing or reading a quote by Frank. Frank has been more than helpful on some of these projects. He makes his own arguments about what to release by virtue of the tapes and the way he made them. "The Purse" on Joe's XMASage is a classic example. Everything you need to know about whether or not Frank would have included certain other things we've got is there. We try to keep the stuff Frank did intact, although we might argue about what should be included in a particular way. And the proof about most of the stuff I've been arguing about is right there in "The Purse." I've been unable to articulate it satisfactorily to Joe, but Frank has delivered it .He makes the best case for most of the stuff I'm adamant about. Most of the Corsaga is just whole chunks of stuff Frank actually edited together.

Joe: And sometimes it isn't.

Gail: Two or three other Joe's Corsagas will come out this year, not that that's what people are jumping up and down about. But we're excited because we think they're really fun. People probably find the titles intensely boring, because everything rhymes, but I dont care. I'm going to keep making them until I run out.

And yes, Joe's Domage [October 2004] is basically a rehearsal tape? but we gave them every fucking clue. I don't want to explain everything.

Joe: Rehearsal tapes have always been traded among bootleggers, and Domage is from a really rare time.

Gail: It's also one Frank carried around. And if Frank could stand to listen to it, I figured the audience could as well. If there's something about it you don't like, try this: Break your leg, sit in a wheelchair, learn how to play guitar in a cast. put that kind of band together, call all your friends, and try to play that shit. That's my advice. And if Frank could do it, what the fuck is wrong with you that you can't take the time to listen?

How did Imaginary Diseases come about?

Joe: The first band I wanted to dive into after I was given my Vaultmeister hat was the Petit Wazoo, simply because it was largely undocumented and very rare. A huge mystery surrounded the band. I wanted to find out what was up with it and how it sounded, so I documented the shit out of all their 1972 tour tapes and put together two CDs with Spencer Chrislu (FZ's in-house engineer during the early '90s] from the original four-track tapes. This was the first tour Frank had the budget to record every show. Prior to that it was very spotty.

Gail: I realized Frank had an idea about some kind of project involving those tapes.

Joe: Then I discovered that Frank had already cut out all the stuff he liked from those tapes. I'd heard the gaps but didn't know what they were. I'd hear it and go, "Whoa, what's going on here?" Eventually I stumbled across actual stereo mixes Frank made from the tour, and we got the machines I needed to play back the stuff I needed to hear. We decided that while there are good performances on the original two CDs we worked on, there were issues with sound quality. We needed to go to the stuff Frank had picked and mixed, whether they're rough mixes or finished and mastered.

Gail: Previously, it would have been something we would have put out on Vaulternative. But it suddenly became something we could put out on Zappa Records. We're not saying Frank would have put the album together the way Joe did. A lot of the time now, Joe says. "Let me put it together and see if you like it." And I think its fair to say I usually do.

Joe: Absolutely.

Gail: I rely on Joe to bring me the head of John the Baptist, and then I see how I want to arrange his curls on the platter. I want to hear everything. If I feel it's missing something, I play around with it, all the time knowing that Joe's falling more in love with whatever he's done and I have a diminishing chance of convincing him otherwise.

Joe: I don't marry myself to it. She has the final word on everything. There's enough Petit Wazoo material for two releases, about two hours' worth. So the first Zappa Records release was authorized by her, handpicked by Frank, mixed by Frank, and produced for release by myself.

What's your opinion of bands covering Frank's music onstage, as Phish used to?

Gail: One thing you fight for as an artist is that you get paid for your work. Here's the way I look at it: They're playing Franks music and I'm not getting paid. Frank did not write it for them to play without paying him, so they sure as fuck should have paid me. It's small money to perform it, cents on a dollar. That's what I don't understand. Why wouldn't they want to do right by the artist? What do they write music for? Do they buy groceries for their kids? Well, so did Frank Zappa.

I take it that's how you feel about anyone playing Frank's music?

Gail: In America every day rock musicians fuck people over by not turning in their setlists for licensing. They're much more stringent in Europe. Don't get me wrong. I love people covering Frank's music. But I want them to license it, I want them to get permission, and I want them to pay.

Most of the bands would say they're not making much money at all playing Frank's music in public.

Gail: I think the biggest hit outside of Frank's own records has been the Gotan Project's "Chunga's Revenge" [on La Revancha del Tango] — and they added lyrics without permission! What the hell's that about? It's always something. It was the same for Frank. Because when you have to deal with the day-to-day shit people dump on you, it is not fucking fun at all.

The most fun I have is sitting down and listening to Frank's music in the studio with Joe. And the most fun Frank had was making records or playing live. Like the jam with the audience at the beginning of Imaginary Diseases — he pretty much invented that. The downbeat happened when his feet landed on the goddamn floor of the stage, and then it just came at you like a fucking train — a whole bunch of them — rolling out of the station and right over you. And you're like, Help! What just happened to me? There's nothing like that, and there's never going to be anything like that, that doesn't take you right back to Frank Zappa.

Absolutely Freaked Out

Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention's West Coast Pop-Art Extremism

By Jason Gross

Even his name – Zappa! – sounded like a superheroic exclamation. How fitting, then, that Frank Zappa, with the assistance of a heretofore unequaled auxiliary freak squad, elevated pop-music antics to high art during what many fans – including me – still consider his most inspired period. In various configurations, the original Mothers of Invention released seven remarkable albums in their four years together and altered the course of rock forever. Zappa radically stretched the medium's limits by assuming a variety of roles that made each Mothers album an increasingly wonderful and bizarre musical stew.

Zappa As Greasy Doo-Wopper

While Chuck Berry lit a fire under hordes of '60s rockers, Zappa's influences stretched back to early-'5Os rhythm-and-blues. He concocted a twisted version of oldies music, having over-the-top singers howl, moan and croon determinedly cheesy lyrics that might have made The Coasters blush. Such hilarious numbers as "Any Way The Wind Blows" and "You Didn't Try To Call Me" from the Mothers' 1966 debut, Freak Out! would be reworked as more orthodox doo-wop fare on Cruising With Ruben & The Jets two years later. While the originals were ace parodies, the Ruben re-makes didn't sound as lively: the satire's cute but less biting, and it all sounded a little too lovingly faithful. Zappa's doo-wop shenanigans would reappear the following year on both March 1969's Uncle Meat ("The Air," "Dog Breath, In The Year Of The Plague") and December's Burnt Weeny Sandwich ("WPLJ," "Valarie") with just the right amount of kitschy fun.

Zappa As Wacko Maestro

At the same time as The Beatles, Pink Floyd and The Who were slowly nudging rock into the realm of A-R-T, Zappa was diving into it headlong. With old European masters like Ludwig Van and Wolfgang Amadeus providing highbrow pop's classy face for the most part, Zappa's heroes included such 20th-century revolutionary geniuses as Edgar Varèse, John Cage and Igor Stravinsky at a time when they were still regarded by many as outcasts, weirdos or worse. Zappa quotes ol' Igor's Rite of Spring and Petrouchka all over 1967s Absolutely Free and name-checks him on Burnt Weeny's "Igor's Boogie." Varese's psychopercussive music underlies just about every Mothers record, especially Zappa's other 1967 release, Lumpy Gravy. By the time of February 1968's We're Only In It For The Money, Zappa's wild tape/electronic experiments were providing sometimes abrasive interludes and interruptions he would mostly abandon after 1969's Uncle Meat.

Zappa could also lay claim to being the Dr. Frankenstein responsible for an oft-maligned monstrosity: the concept album. Absolutely Free included suites devoted to lust for vegetables and the zombification of America's teens. While We're Only In It For The Money (savor that amusing, insulting title) was packaged as a spot-on spoof of The Beatles' recent Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, the album s real antagonists were a stateside authoritarian government and pathetically shiftless youth culture – kind of like today. Recorded as a Zappa solo album around the time of Money, late 1967s Lumpy Gravy was assembled from (too many) short, fractured snippets, some of which would creep into other Mothers albums. Neither side-long suite s stoned conversations, Varese worship and sludgy blues are as satisfyingly rounded as Free or Money. After the first few Mothers albums, Zappa crafted the band's remaining '60s output as collections of far-flung tracks instead of grandiose unified concepts.

Zappa As Unapologetic Fusion Pioneer

Next to disco, no '70s music bugs haters as much as jazz-rock. Like Miles Davis, though, Zappa was on the fusion tip in its loud, raging infancy, unleashing it briefly on Absolutely Free ("Invocation and Ritual Dance of the Young Pumpkin") before ramping up to high-powered razz-jock work-outs on Uncle Meat (the sidelong live staple "King Kong") and August 1970's Weasels Ripped My Flesh ("Didja Get Any Onya?" and "Toads of the Short Forest"). Extended jazz-flavored songs were the highlights of Burnt Weeny Sandwich and October 1969 s Hot Rats (a second solo album, augmented with studio pros). "The Gumbo Variations" jumped out on fiats, while Weenys "Little House 1 Used to Live In" featured impressive soloists including violinist Don "Sugarcane" Harris, saxist/pianist Ian Underwood and Zappa himself. Zappa's fusion grew gradually more defuse, though, with the exception of parts of Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo.

Zappa As Third-Party Revolutionary

American History 101: In the late '60s, a second American civil war erupted between the warmongering establishment and peace-loving hippies. Zappa found both sides equally rucked up and conformist. Years before the straight- edge movement, he adopted an anti-drug stance that extended to the Mothers themselves. Starting with "You're Probably Wondering Why I'm Here" (from Freak Out/) and "Plastic People" (from Absolutely Free), he even took the bold, uncommercial step of challenging his own audience s intelligence. He then used most of We're Only In It for the Money to attack mindless hippies ("Who Needs the Peace Corps?" "Flower Punk") and repressive government fascists ("Concentration Moon," "The Chrome Plated Megaphone of Destiny").

Zappa's allegiance lay instead with "the freaks." He championed a community of Southern California pre-hippie bohemians who dripped nonconformity and created instant parties wherever they went. Freak Out/ bears their name, starting with a threat from the weirdo masses ("Hungry Freaks, Daddy") and ending with their guest appearance on a noise concerto ("The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet"). On Money he championed their wild and fearless ways on "Absolutely Free" and "Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance."

Though he shied away from both freak anthems and upfront social commentary for the rest of the '60s, Zappa insisted that social satire continued to lurk in his albums. Only instead of relegating it to lyrics, he was putting it in the music – e.g., Weenys elegant "Holiday in Berlin," which refers sardonically to a German student riot.

–Yoko Ono

Epilogue

In 1969, Zappa disbanded the Mothers – but feel absolutely free to give it up for Billy Mundi. Bunk Gardner, Roy Estrada, Don Preston, Jimmy Carl Black, Motorhead Sherwood and Ian Underwood – because of a) money, b) ego, c) fatigue, or d) all of the above. He subsequently compiled Weeny and Weasels, mostly from material recorded earlier that year. He resurrected the band name in the '70s, though he mostly abandoned the above roles in favor of X-rated thrills, smaller-scale social parodies and lite fusion. He ultimately put the Mothers moniker to rest near the end of the decade, perhaps admitting that their (and his) woolly exploits were over, tied to and reflective of a stranger and possibly more daring time.

Tokens of Buys Extreme

A consumer's guide to Frank Zappa's Post-Mothers Inventions.

By Mike McGonigal

4) Index entry in Ben Watson's Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play (begun): Poodles, xi, xxxi, 50, 229–335, 242, 529, 537, 540; and philosophy, 246–251; as father's penis, 263; as profit fetish, 388–389; as symbol of consumerism, 235–237 ...

After disbanding the (more or less) original version of the Mothers of Invention in 1969. Frank Zappa embarked on one of the most original and prolific careers known to rock. If protest music, art-rock, doo-wop and crazy collaged sounds were all crammed together on the Mothers' 1966 debut. Freak Out!, by the mid-'70s Zappa's myriad proclivities were developing down separate paths. Basically, the dude had at least four separate musical careers governed by seemingly distinct personalities.

Top Ten Titles

Before getting all serious and shit, here are the ten raddest song titles from Zappa's solo era (strenuously and scientifically tabulated, so save your angry letters 'cause we didn't include "Titties 'n Beer"):

- "The Meek Shall Inherit Nothing"

- "Broken Hearts Are For Assholes"

- "Why Does It Hurt When I Pee?"

- "Tryin' To Grow A Chin"

- "Aerobics In Bondage"

- "A Token Of My Extreme"

- "Harder Than Your Husband"

- "St. Alphonzo's Pancake Breakfast"

- "Man With The Woman Head"

- "I Have Been In You"

Zappa's multitudes include the avant-rock jazzbo cat who made meticulously difficult but highly listenable albums like Waka/Jawaka and Hot Rats; the Straight/Bizarre/DiscReet record-label honcho with a penchant for extreme and unorthodox talent (e.g., Alice Cooper, Captain Beefheart, Wild Man Fischer); and the classical composer not taken that seriously in his lifetime — perhaps because of everything already mentioned. Of course Zappa also laid down some of the meanest, meatiest guitar this side of Jerry Garcia, Carlos Santana and John McLaughlin. And finally there's the satiro-pop comedy fellow who recorded "Disco Boy," "Valley Girl," and that song about where the huskies go and yellow snow that your cool stoner older brother hipped you to one night when your parents weren't around, the one you still find kind of funny even though it's pretty stupid when you get right down to it.

You don't have to be a total Zappa obsessive to dig him, of course. Actually, the crappy stuff generally only suffers from one of two faults. Like your estranged uncle, it may be smirkingly funny sounding while really not that funny at all. Or there are just far too many notes that go on for far too long.

Frankie The, Uh, Pimp

Frank was an unabashed champion of some of the planet's least "ept" outsider musicians. He lauded the wonderful Shaggs as "better than The Beatles." He produced brilliant eccentric Captain Beefheart and The Magic Band's mind-bending double album Trout Mask Replica. And he unleashed uncompromising performance art LPs by The GTO's, Lord Buckley and Wild Man Fischer onto the world on the Bizarre and Straight labels. As producer, Zappa even worked with Grand Funk Railroad on their misleadingly titled 1976 album Good Singin' Good Playin', though he chose not to produce other people's work after that.

But where to start with his ridiculously large oeuvre? The following ten essential Zappa albums toggle between his split personalities, which of course do overlap and eventually smear together info ye olde conceptuale continuitie.

5) 43 Words from Them or Us (The Book) (1984): "It is not for intellectuals or dead people. It is designed to answer one of the more troubling questions related to conceptual continuity: "How do all these things that don't have anything to do with each other fit together, forming a larger absurdity." – introduction to 394-page self-published book.

Make A Jazz-Rock Noise Here

While one should ordinarily run screaming from any jazz-rock not recorded by Miles Davis in the early '70s, Zappa's period work in this vein is a welcome exception to the rule.

1. Waka/Jawaka (July 1972)

Holy frijole! This album nails the space between composition and improvisation perfectly and makes a fine companion piece to 1969's Hot Rats. Sal Marquez's trumpet playing is especially stellar throughout. The album was recorded by a shit-hot group of LA. studio pros during spring '72, the year FZ spent in a wheelchair after being thrown off a London stage by an enraged fan.

2. The Grand Wazoo (November 1972)

Fancy-ass space boogie, SoCal style. More music from the wheelchair period, these small orchestral works sound more composed but jazz-rock no less exceptionally than Waka does.

3. Roxy & Elsewhere (1974)

This live prog-rock masterpiece mixes colorful fusiony funk ("Village of the Sun") with farther-outeries ("Don't You Ever Wash That Thing?") and funny jam songs ("Penguin In Bondage").

Orchestral Favorites

Rockers writing classical music are like actors who really want to direct (take heed Joel, McCartney, Waters and Costello). Zappa fares best in this department, though his own orchestral works, inspired heavily by Igor Stravinsky and Edgard Varèse, often sound meandering, unfocused and precious. Only 52 when he died, alas and alack, his work would have almost inevitably developed, evolved and matured.

4. London Symphony Orchestra (1983)

If you consume one Zappa classical disc, make it this one. A certain peculiar whimsy is evident in works performed by the famed limey orchestra under the direction of Kent Nagano, especially in the strange and soundtracky "Pedro's Dowry."

His Guitar Wants To Kill Your Mama

Did we mention Zappa's thoroughly sick guitar talent?

5. Shut Up n' Play Yer Guitar (1981)

All guitar solos, all the time. The selections on this three-CD set fade in right before the solos and fade out right after. What would be an inter- minable exercise for any other player sounds perfectly righteous here. Zappa's mind clearly worked at lightning speeds, and the acoustic tunes with a short-lived trio are simply gorgeous.

6. One Size Fits All (1975)

The (over)slickly produced studio companion piece to Roxy & Elsewhere contains some of Zappa's finest guitar, especially in the minstrelsy "Po-Jama People."

Does Music Belong In Humor?

Zappa's most infamous songs ("Yellow Snow," "Dancin' Fool," etc.) are not his best work by any stretch. That said, there's something benignly perverse about a total brainiac fixated on politically incorrect humor and bodily functions of all description. It would be nice if he came across as a little less misogynistic and a little more, oh, culturally astute. Yet FZ's parallels to smarty-pants bad boys like Rabelais, Howard Stern and Alfred Jarry are obvious. Zappa's contempt for political, religious and fashion-damaged hypocrites of all stripes was notorious. He often seemed incapable of censoring himself, for better or worse. What follows are the "betters."

7. You Are What You Is (1981)

This Reagan-era time capsule is the smartest, if most seemingly chauvinist, of the skit-heavy "Frat Zappa" albums. A sociosexually conceptual Joe's Garage, it manages to offend posers of every sexual persuasion equally.

8. Fillmore East, June 1971 (1971)

Flo & Eddie (Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan from '60s group The Turtles) run amok as goof-ball musical theater kids. Their reggae version of their former band's hit "Happy Together" milks bombast and irony at the same time, while "Mud Shark" recounts the infamously disgusting Led Zeppelin groupie story.

9. Apostrophe (') (1974)

Zappa's highest-charting album is the template for all subsequent joke-rock excursions: tight, vampy tunes with playful lyrics try really hard to incite while amusing. Feel free to avoid Stink-Foot" when you download.

10. Sheik Yerbouti (1979)

Frank himself dubbed his high-concept comedy rock "dumb entertainment" And his very un-PC, second-highest-charting release (which might have something to do with why he made them in the first place), with songs like "Jewish Princess" and "Yo' Mama," is definitely both dumb and entertaining. Huzzah.

Up The Wazoo

Zappa Records kicks off with The Best Little Big Band You Never Heard In Your Life

By Christopher R. Weingarten

– Jon Gutwillis, The Disco Biscuits

The only thing bigger than the legacy Frank Zappa left behind was his library: miles and miles of unheard music, tidily labeled and organized, stashed away in a climate-controlled vault somewhere in the fertile LA. soil. To say that anticipation of this unreleased material runs high — full albums mixed by Zappa and ready for release! Eons of immaculate concert audio! Secretive projects discussed only in whispers! — would be like calling the Ebola virus "a nasty bug." The rumored stellar recording quality of this near-limitless output would make Dick's Picks seem like a school of water-damaged C-90s floating belly-up in a pool of bongwater.

– Gary Lucas, Gods And Monsters

Snacks have been trickling sporadically from the vault thanks to Gail Zappa and tireless Vaultmeister Joe Travers, whose hapless eardrums have been poked by an unfathomable number of audible oddities since snagging the gig in 1995. The bubbly new Zappa Records logo is a reassuring sight on first release Imaginary Diseases, a collection of 1972 live performances selected and produced by Frank himself. Stuck in a wheelchair after a surprise collaboration with the bottom of a 15-foot-deep orchestra pit, the immobile, restless Zappa explored compositional efforts that year, resulting in Waka/Jawaka's brisk jazz-rock fusion, the unreleased Hunchentoot sci-fi musical (likely napping in the vault somewhere), and the unmitigatedly audacious 20-member touring nightmare The Grand Wazoo. For the sojourn collected on Diseases, Zappa stripped the unwieldy collective to a crisp, ten-man machine billed as the Mothers of Invention but known to Zappaphiles as the Petit Wazoo.

6) Two Chords from "Louie Louie" (part 1): See: between Motorhead monologues (Lumpy Gravy, 1967); the President of the United States (Absolutely Free, 1967); Don Preston at the mighty, majestic pipe organ at the Mothers of Invention's 1967 Royal Albert Hall debut ...

Pristine recordings and ferocious improv make Diseases as invaluable as any Zappa live document, especially since the low frequencies give live jams like "D.C. Boogie" a little extra, well, boogie. Zappa's half-dozen horn footers explode in pyrotechnic soloing on the 16-minute centerpiece, "Father O'Blivion." A trombone quavers like a theremin, a trumpet whines like a lonely dog and Apostrophe (') drummer Jim Gordon lays into his kit with crowd-pleasing crescendos — no heady chops wank, just heavily hammered discharge. An echoey live jam from Montreal resounds off the walls of the Quebec Forum during a gig that also featured Tim Buckley and Curtis Mayfield , terrorizing listeners with a groove heavy enough for the latter to love. Even funkier is the title track — exclusive to this tour and previously unavailable on any Zappa release — Zappa's booty-movingest moment since "Willie The Pimp." No wonder George Clinton loved the guy.

To satiate true Wazoonatics, Vaultmeister Travers also excavated a period rehearsal tape for release on the more obsessives-indulgent Vaulternative label. Released as Joe's Domage, the recordings document Zappa attempting to get the earliest Waka and Wazoo germs afloat, his eight-man team (all but Mothers keysman Ian Underwood would end up on Wazoo) struggling with their parts. With Zen-like patience, a wheelchair-bound Zappa teaches the band the score while they coalesce into an unholy blob-poking, prodding, and tweaking until finally, and gloriously, taking off. Its great to hear these perfectionist pros play sour notes, bungle tempos and work out particularly gnarly phrases while gestating punchy embryonic versions of tunes like "Blessed Relief." This imperfect peek into the composer's creative process remains a fascinating document full of unrepeatable rawness.

7) Four Variations on the "Little House I Used To Live In": Introduction published in the October 1969 Down Beat magazine ("a piano exercise dated approximately 1962"); intro, themes A-B-C (Burnt Weeny Sandwich, 1970); "Return Of The Hunch-Back Duke," containing themes B-C (You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 5, recorded 1969); "Twinkle Tits," performed in 1970, contains theme C; "Concerto For Mothers And Orchestra," performed in 1970, contains intro motif.

(Courtesy Michael P. Dawson's Biffy Page.)

While fans hold their collective breath for gems like the complete Halloween 1981 concert, Travers has discovered ephemera offering all-important Conceptual Continuity Clues in candid cannisters Frank probably (frankly?) never intended to be heard. As one naysayer on the official FZ message board put it: "What's next? A tape of Frank and the family having a barbecue?" While Joe's XMASage, a compilation of seemingly random 1962-64 recordings, has its share of goofing-around-as-socioanthropological-experimentation (i.e., Frank taping his buds), it also contains fascinating insight into his earliest work — gothy R&B, go-go bar jams and some of his most visceral electroacoustic experiments ever. Minute-long tape manipulations sound impossibly mature for stuff likely tweaked out on Studio Z's homemade five-track, with "The Moon Will Never Be The Same" sounding uncannily like his hero Edgar Varèse and "Mousie's First Xmas" turning haunting clarinets and tape splices into a moody John Cage nod. And the regular-acoustic stuff is even better: "GTR Trio" adds a full nine minutes to the "Bossa Nova Pervertamento"-jam on Mystery Disc, with Zappa picking and clawing his way through a riotous guitar solo, playing cement-fingered Latin jazz all gassed up on dirty blues and dirtier clothes.

Jamming In Joe's Garage, Part 1

Sharing Studio and Stage with Zappa in the 80's

By Steve Vai

8) Three Quotes From Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring" See: "Amnesia Vivace" (Absolutely Free, 1967); "Fountain Of Love" (Cruising With Ruben & The Jets, 1968); "In-A-Gadda-Stravinsky " (Guitar, 1988)

Simply put, Frank Zappa was – and is – the most extraordinary person I have ever known.

My first taste of Frank's music was "Muffin Man" from Bongo Fury. I was captivated from the opening line – "The Muffin Man is seated at the table in the laboratory of the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen" – delivered by Frank in his inimitable way. Here was something that scratched an itch nothing else could even remotely reach, music that encompassed exceptional elements of rock groove, wild guitar playing, dense composition, political satire, comedy and achingly sweet melodies – as well as some beguilingly ugly ones, too. Frank loved to make light of the inane and foolish things many people do and believe, and I sure got a kick out of that. And while much could be said about Frank's political views and impact in that arena, what gave me the hardest wood was his music.

I immersed myself in Frank's exquisite sonic elixir throughout my preadolescence. His creative output was bafflingly, even bewilderingly, rich. He seemed to lack boundaries completely, and he never catered to tradition or norms. On the contrary, he'd go out of his way to poke fun at them and could cut to the heart of hypocrisy in any form.

In 1975, I got Franks home phone number from a friend who'd heisted it from a posh New York City recording studio's Rolodex. I was 15. Once I had the number, I'd call Frank's house every few months but never got him on the line. Then one day, after nearly two years of trying, he finally answered – and he was in a good mood, too!

He agreed to accept a tape of mine and, several months later, asked me to audition for his band. When I told him I was 18, though, he said, "Forget it" But he did hire me to transcribe lead sheets, scores and guitar solos.

I moved to Los Angeles a couple of years later, and after visiting him in his home studio in Laurel Canyon to record, he invited me to try out for his band. This was all quite unbelievable to me, so I just went on autopilot and did my best to play his music the way he wanted it played.

"What inspires you to make your music?" and "How do you do it?" are questions frequently asked of successful musicians. Frank seemed inspired by everything and anything, and nothing deterred him when it came time to channel his muse into an audible reality. He twisted technology while deeming no subject immune to his incisive lyrics, and the pure expression of his unique vision never stopped evolving.

In his studio, also named the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen (UMRK). Frank was the most elite of audio gourmet chefs. He disregarded convention while possessing a wizardly approach to invention. He took existing technology and brutally stretched and flagellated it until it screamed for mercy.

His methodology included merging tracks recorded by separate bands with tracks borrowed from previous records, reassembling tracks from various live recordings (sometimes even backward; check out "Ya Hozna" from Them Or Us), layering massive vocal overdubs, and processing sounds to an unrecognizable – but perfectly applied – sonic tapestry. At the core of it was always a hook, and that hook was the essence of Frank's personality running through everything he manifested. Allowing that essence to permeate your intellect and your senses is the best way to get to know and love who he was.

Frank was first and foremost a composer. He taught himself orchestration and would redefine conventional harmonic and melodic ideas. His profound ability to dissect rhythmic notation set new standards. It wasn't unusual for Frank to combine two challenging pieces and ask us to perform them simultaneously, such as "Manx Needs Women"/"Approximate" on Zappa In New York. Or see bar 15 of "The Black Page," where he superimposes a half-note triplet on top of a bar of 4/4 time and notates nested tuplets within it. If that sounds complex, well, it is. On top of this technical polyrhythmic extravaganza, the melody is profoundly enchanting.

At rehearsals, Frank would either deliver written music for the band to learn, demonstrate parts on guitar, or sing them to us. My favorite rehearsal memories, however, are the times he'd arrive with just an idea and then construct a song such as "We're Turning Again," "The Blue Light," or "Tinseltown Rebellion" around it. He combined a teenager's zeal with unqualified genius at these sessions, and it was marvelous to behold. Bursts of laughter would constantly interrupt the proceeding, and a good time was had by all.

God, did I love Franks guitar playing. He seemed to take a more visceral approach to his solo constructions than to his written music, regarding his solos as spontaneous compositions. Guitar pieces such as "Zoot Allures," "Black Napkins," and "Watermelon In Easter Hay" are so beautiful it hurts. For three solid tours during the early '80s, I was fortunate to stand alongside of him for no less than one hour of total soloing per night, and I basked in the vibrations of his guitaristic splendiferousness.

Franks compositional evolution eventually manifested itself in constructions for the Synclavier, one of the first totally digital recording workstations. If you listen to such brilliant Zappa albums as Jazz From Hell or Frank Zappa Meets The Mothers Of Prevention, or any of the two thousand or so finished or unfinished compositions still residing in his Synclavier, you can hear a great composer continually busting the boundaries of contemporary composition.

It's said that most great composers reach their creative peak between the ages of 50 and 70. Frank passed away at age 52, and it's impossible to even begin to imagine the kind of work he'd have produced. The world was robbed of untold musical magnificence. I truly believe that a century from now, when most currently popular bands are little more than funny names from the past, Frank's music will be studied by scholars, included in every curriculum concerned with great music, and performed by musicians the world over with the respect and awe due their resplendence.

And because I'd like this article to function more as a kind of public service than as simply one more tribute to the enigma who wrote "Dinah-Moe Humm," I heartily encourage you to treat yourself to Frank Zappa's vast catalog of incomparable music. Because if you discover yourself resonating with his music, treasures beyond measure await to enrich your soul – seriously, folks.

The only tough part will be deciding where to start. So how about here?

Ah heck, it's all amazing!

Jamming In Joe's Garage, Part 2

The Last Stunt Guitarist remembers the Final Tour.

By Mike Keneally

In late 1987, Frank Zappa hired me to play guitar and keys in his band – a 12-piece group with five horn players. We were the last rock band Frank would take on the road.

After I joined, we rehearsed for four months: eight hours a day, five days a week. After years of mostly playing keyboards, I spent much of this period attempting to make a musically useful tone with a guitar and an amplifier. And while I went through many amps in search of a sound that worked, at least the guitars were happening – two of Franks own: a customized Stratocaster and an incredibly sweet-playing Tele. I loved playing the insane "Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue" and "Alien Orifice" melodies on this buttery Telecaster; it felt good and unexpected to play these crazed parts with a mellower tone than earlier Zappa guitar monsters such as Steve Vai, Warren Cuccurullo and Adrian Belew had used. The tone was partly a concession to band timbre (the outrageous horn section dominated the midrange frequencies, so I tried to surround their sound) and partly due to my sheepishness about holding down a position previously occupied by such forceful stylists as the abovementioned deities.

I was also coming to grips with the arcane and dangerously precise mathematical realities of Franks composing. Entire musicological universes exist in those freaking songs. I'd absorbed most of Frank's music through feel, and had never seen any charts, so I didn't have a fully formed awareness of exactly how the music was written; a lot of those note groupings are very specific, insanely complex, and difficult to decipher without a transcriptionist's ear, which I didn't have at the time.

During my first rehearsal with the complete band, I toiled to make logical sense of a series of quintuplets in the piece "Filthy Habits." While the version on Sleep Dirt consisted of a solo-guitar passage I hadn't processed as evenly phrased five-note groupings, Franks new arrangement had specific and tight unison playing from the whole band. I chumped four successive attempts before Frank stopped the band, looked directly at me and asked, "Why is this so HARD for you?" That was the entire conversation and it worked – I did everything I could to get my shit together quickly from that point on.

I still encountered an extremely steep learning curve during the months of rehearsals, however. I was constantly trying to figure out how to do ANYTHING, yet Frank was thoroughly patient and encouraging, to my extreme gratitude.

He was a hell of a bandleader, and I stood gape-jawed in amazement as he assembled this music, crafting advanced and exciting arrangements spontaneously for a 12-piece band in mere moments. For me growing up, Zappa was THE GUY, and it was mind-blowing to help make a new tour happen, especially one few fans dared dream would ever happen. After a financially wounding 1984 tour, Frank had sworn he would never tour again.

A couple of weeks before the 1988 tour began, I sat with Frank in his basement. Here I was, an utter novice with no professional musical experience of note, no inkling of tour life, and no clear idea of what it would take for me to help, rather than hinder, Frank's work. Perhaps sensing this, he summed up exactly what was at stake. "People who come to the shows" he informed me, "expect to be BLOWN AWAY." While his musical priority involved making sounds he enjoyed, Frank was also completely invested in exceeding his audience's expectations and using every tool at his disposal to do so. He got off on making people ecstatic through music, and I was getting excited, too.

–"Weird Al" Yankovic

We played two months on the East Coast followed by two months in Europe. The tour opened in Albany, New York. Amazingly, I don't remember being overly nervous. I was happy, grateful and pretty much giddy all night long. Everyone seemed euphoric backstage during intermission. A strong sense of band unity (which sadly dissipated during the course of four months on the road) prevailed, and Frank was visibly pleased – a big old smile on that face was always a welcome sight. The crowd, delighted to see a Zappa show after he'd foresworn touring, loved it. Indeed, what better return to the road than with this large, fiendishly well-rehearsed band playing remarkably ambitious arrangements? And the whole thing was completed beautifully by the blessed sight and sound of Frank playing deadly solo after solo on his gorgeous-sounding, crystal-clear, and unapologetically LOUD lead guitar. For me, heaven.

For some reason, Frank chose my first-ever professional musical performance in front of more than 50 humans to repeatedly throw the musical spotlight on me during the second set, tossing me solos where I didn't expect them, engaging me in conversation, and making me improvise on guitar, synthesizer and voice simultaneously. For our show-closing rendition of "Stairway To Heaven," he requested that I finish the song on my knees at the front of the stage. I felt shy but went for it anyway – he did indeed have a way of getting people to do things. We left the stage, returned for the encore and the first thing Frank said was, "Mike Keneally, ladies and gentlemen!" I've experienced many ups and downs since then, but that memory still evokes levels of gratitude I can't describe. I thank all people/deities involved that I was able to experience Frank Zappa in my lifetime, and I continue to be nourished in every way by my association with him. Hooray.

Zappaesque

Or the Story of the Sots

By Matthew Van Brink and Jesse Jarnow

Like The Beatles and Bob Dylan, Frank Zappa has entered the realm of the critical cliché by becoming what your local librarian might call a descriptor – the music of almost anyone interested in peculiar/ambitious combinations of prog-rockery and humor will forever be dismissed as Zappaesque. Unlike The Beatles, however who were once accused of employing an "Aeolian cadence" on "She Loves You" without having the foggiest notion of what that was, or Dylan, who consistently insists upon his faith in the moment, Zappa was a composer fully conscious of his own voice.

So what is this Zappaesque? Cartoon music for cretins? Doo-wop for weirdos? Rock from another dimension? Zappa, as he was fond of saying, organized black dots on paper. What made him Frank, though, was his particular manner of connecting them together in such a way that they would sound, as he put it, "bitchin'."

Zappa had his own style for each type of connection, be it harmonic (how dots relate vertically on a musical staff), formal (the way one group of dots relates to other groups), temporal (the pace at which musicians read the dots across the page), or textural (which dots come out of which instruments).

Zappa can often be identified by his constant self-interruptions, where melodies unexpectedly veer into jarring cinematic flourishes before resolving back into proper songs. Igor Stravinsky used similar techniques in "The Rite of Spring" (1912), one of Zappas favorite works, wherein Igor boogies magnificently between musical ideas and textures.

While Zappas musique concrete masterpiece, 1967's Lumpy Gravy, consists almost entirely of unresolved interruptions, its probably easier for all of us to grok "Inca Roads." the first track on 1975's deceptively populist One Size Fits All.

— Jake Cinninger, Umphrey's McGee

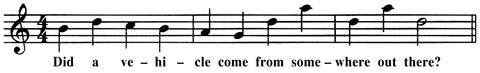

Laid over a cool vibraphone groove, Napoleon Murphy Brock's vocal leaps in fifths from smooth quarter notes to jagged syncopations (ex. A). The interruptions occur between the verses. The first alternates between wildly precise full-band runs and vamping vocals (ex. B). The second interruption even interrupts itself, flashing back to the song's verse for a did-they-really-do-that? moment between off-beat triplets and another full-band sexy-time explosion.

Zappas guitar solo is likewise an extended interruption floating over C2, an unresolved chord that pulls the ear along with a sense of delayed gratification. It was a characteristic harmony for Zappa, who used it frequently in, for example, Waka/Jawaka's title track (1972) and in his daredevil challenge to instrumentalists, "The Black Page" (1978).

Written for stunt drummer Terry Bozzio and named for its remarkably dense profusion of dots, "The Black Page" was beloved by Zappa for its "statistical density" Steve Vai even earned a gig with Zappa for being able to transcribe and play the song (albeit really, really fast).

It's fun to compare a segment of "The Black Page" (ex. D) with a chunk of Integrales (ex. C) by Edgar Varèse, another of Zappa's favorite composers.

–Jeff Austin, Yonder Mountain String Band

What Zappa might have picked up from Varese – whose Ionisation (1929-31) was FZ s first exposure to the avant-garde – was a predilection for spasmodic rhythmic profiles. But where Varese s music grew out of the world of classical concert performances, Zappa's was a product of the rock era. The four-minute "Black Page" is based on a series of dazzlingly rapid tuplets – or, as Zappa quipped of his creation in The Real Frank Zappa Book, "Monday and Tuesday in the space of Wednesday." Zappa's rhythms pile up dramatically, making the piece proceed ever faster and busier to its orgasmic conclusion. "To be able to write a piece of music and hear it in your head is a completely different sensation from the ordinary listening experience," Zappa wrote in his autobiography. Frank liked dots, and why wouldn't he? They bent to his composer-guitarist will. They understood his intentions, even when nobody else did. More than a decade after his death, one can follow the inky roads back to Zappa's innermost abstractions, past the Mothers and their inventions, beyond the Valley of Poodles and Blowjobs, to the cosmik debris within.

'9) Two Chords from "Louie, Louie" (part 2):' See: You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 1 1988, Broadway The Hard Way (1988), or, well, just about any performance of the 1988 band; "Welcome To The United States (The Yellow Shark, 1993).

10) Three Bottles of Ketchup See: The cover of Them Or Us (1984); the cover of The Perfect Stranger (1984); as a vegetable (according to Ronald Reagan, anyway) on "When The Lie's So Big" (Broadway The Hard Way, 1988).

11) Three Mud Sharks (Rock Anthropology Subset) See: Fillmore East, June 1971; "Be-Bop Tango" (Roxy & Elsewhere, 1974); and interview with manager of the Edgewater Inn (Playground Psychotics, 1922).

Dweezil Plays Frank

By Richard Gehr and Dweezil

Dweezil Zappa is the new head chef at the state-of-the-art recording studio his father Frank, dubbed the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, located in the lower level of mother Gail's Laurel Canyon home. Upon my arrival, he cranks up a work in progress titled "Rhythmatist," a whirlpool of fiery electric guitar and sampled orchestral Instruments. It sounds like a single glorious riff deconstructed a thousand different ways and contains an unmistakable genetic echo. An accomplished rocker and occasional TV personality, the 35-year-old has been assembling a band and practicing guitar in anticipation of his center-stage role in the upcoming Zappa Plays Zappa tour with younger brother Ahmet.

What is Zappa Plays Zappa and where did it come from?

My mom and other family members have talked about it for a long time. But the fact of the matter is that it couldn't happen until I was able to do it not only physically, but also emotionally. Because I'm going to have a hard time going out there. Certain songs just hit you and I'm going to struggle with that. But I think l'll be able to prepare for some of that as we rehearse over the next three months.

It's going to be a band of newcomers with some familiar faces sitting in for mini-sets. Steve Vai, Terry Bozzio and Napoleon Murphy Brock will appear on a nightly basis. We'd like to do this on an annual basis. We're trying to build a new fanbase as well as reach out to the core fans. It's been more than 14 years since the last official Frank Zappa musical event.

[[Image:Framewidth.jpg|frame|"Frank Zappa was the rock guy who plastered classical, highbrow, blues, lowbrow, reggae and gawd knows what else into a style uniquely his own. Beside the juxtaposition of many diverse, seemingly unrelated styles, he possessed a strongly developed compositional 'signature' consisting of heretofore-unimagined rhythms and melodies typically performed at knuckle-busting, blowtorch-to-the-head speed. His guitar tone and style are immediately recognizable – honking, stinking. loud and delicate with flourishing, ornate, melodic, knuckle-dragging inspiration in every note."

— Chuck Garvey, Moe.

Are you going to attempt to recreate Frank's guitar style?

I'm building my own guitar rig to recreate some of those sounds, or at least get me in the ballpark to play stuff that fits the context of his music. I have a different style, but when it comes to playing Franks music, you have to make sense in the idiom. I've also been learning interesting marimba and keyboard melodies that Frank never played.

Frank had a couple of things unique to his style, strange note groupings, articulations and a picking style I can't imitate because it was so unique to him. I describe it as the battle between the chicken and the Spider. He'd allow a scraping thing to happen while he was picking. The core of his guitar style was a blues element. He wasn't the type of player who stuck to a single signature style, like George Benson or Eddie Van Halen. His signature style and tone is more difficult to emulate because it comes from an entirely different thought process and a certain emotional response. When he plays a solo, he thinks in terms of air sculpture – shapes like rectangles and oblongs – while at the same time listening and reacting to everything else that's going on. Most guitar players are just like, "Hey, check me out!"

[[Image:Framewidth.jpg|frame|

Fourteen Possible Instances Of Conceptual Continuity:

12) Optional Cognitive Dissonance Waitaminute, dude, doesn't, like every artist or musician or writer keep working with the same material over the years? Isn't his notion of Conceptual Continuity just a smart-ass way for Zappa to get us to buy all his records and ...

13) Turns Out He Was Obsessed With Poodles The 1977 "Poodle Lecture" is a Zappalogist's Rosetta Stone. See: You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 6, and Baby Snakes DVD.]]

He also had a distinctly captivating guitar sound, too, no matter what he was playing.

I heard an interview where he talked about spending $30,000 to build his guitar rig in the mid-70s, which is like $200,000 today. Frank performed with studio-quality gear a decade before it caught on. He had parametric equalizers installed in his guitar so that its sound would cut through the arrangement onstage, and he used a four-track tape machine to return slap-back delay to the audience in quad. He always wanted to create a listening experience that was much more enjoyable than a typical rock show. He was interested in the science of it.

His guitar rig always had a clean direct signal he would mix into his regular guitar sound so you could hear more articulation, string noise and picking noise. Then he could take that direct signal into the studio and re-amplify it and mic up a speaker to create an entirely different guitar sound, which he could layer up. There's so much depth to his lead guitar sounds on records that they sound doubled. There s a slight bit of delay, so the direct sound gets to your ear faster than the recorded sound, which created spatial anomalies, which he was always into. Short delay times trick your ears and make things sound wider and bigger and three-dimensional. He used all of that in his recordings.

One of Franks all-time best guitar sounds is the solo on "Watermelon In Easter Hay" from Joe's Garage. It combines direct guitar, reverb and other stuft, and the melody is so striking I can't even listen to it because it reduces me to tears. I can't even think about it.

You recorded your first album at 17, had your own band for several years, Jbut then seemed to fall off the map, at least musically. What got you back into playing and composing again?

I realized a little too late that I needed to know more on a technical level. And by "too late" I mean I didn't know what I know now while Frank was still around, and that's such a shame because I could have had such interesting conversations with him and taken my music to a whole other level. I developed a lot of technical ability in a short period of time and hit a plateau. The music industry changed in terms of what people wanted with guitar, so I stopped playing guitar and played more golf. I got back into music again by getting into Frank's music, and into computers. Now I can create amazing arrangements to play cool guitar stuff over.

Perhaps to avoid pretension or obscurity, his comedic stuff always offset his musical hyper-sophistication. Whatever the reason, it made sense. He was an inspiration, in short, and anyone touched by his work will be the better for it, now and forever."

— Wayne Krantz

Not unlike Frank's transition from bandleader to Synclavier soloist.

Frank understood the scientific components of sound from the molecular level up and he knew how to recreate them in the digital worid. Frank needed the Synclavier to play music too difficult for musicians. He eventually ended up with the last version of what could be considered a Zappa band, the Ensemble Modern. For The Yellow Shark, he got to rehearse with them as much as he would with a rock band. Listen to "G-Spot Tornado" and compare it to the Synclavier version from Jazz From Hell. It's even more brutal when real people play it, with notes whizzing by fast and furiously. That's one of the songs we're working on and I consider it one of Frank's signature compositions.

Which Frank Zappa records would you suggest to newbies overwhelmed by the options available?

I typically recommend Apostrophe (') and Over-Nite Sensation because they're great records from a very creative period in terms of blending orchestral concepts with rock-band arrangements. Both records sound cool and have a rock grooviness a lot of his records seem to be developing until that point. It was a memorable period for complicated and sophisticated songs that are also fun, melodic and easy to listen to. They take you on ajourney. When people are hit with too much information, they shut off. But people who really like Frank's music can't get enough information from that world. They love the details, how it all comes together.

'14) Index entry in Ben Watson's Frank Zappa - The Negative Dialectics Of Poodle Play (concluded):‘‘‘ ... audience as poodle, 477; Breeding From Poodle, 409–410; fabulous, 392; new explicitness in Zappa, 229; servility of 234–235; the site of punished nature, 361.

Special thanks to Jesse Jarnow for Fourteen Possible Instances of Conceptional Continuity and to Mike Greenhouse for artist tribute quotes

What was Frank like as a dad?

He was inspiring. The amusing thing was that he was like an encyclopedia. You could go to him with homework and he pretty much knew anything you needed to know, and then some. He'd give you a good example that would make you more interested in the subject. Once he tried to punish me by making me watch televangelists. That kind of backfired, though, because I thought they were really funny. He was great at a word game we liked to play, like Sniglets, where you create a word out of concepts. One time we wondered what you'd call the kind of individual who loves to wear rock T-shirts, the sort of person who can't wear a shirt without a logo. And Frank, without batting an eye, said insignoramus.