Difference between revisions of "The Zappa Legacy"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | By [ | + | By [https://www.facebook.com/bob.doerschuk Robert L. Doerschuk]<br> |

[[Keyboard]], April 1994<br> | [[Keyboard]], April 1994<br> | ||

Revision as of 21:29, 4 September 2021

By Robert L. Doerschuk

Keyboard, April 1994

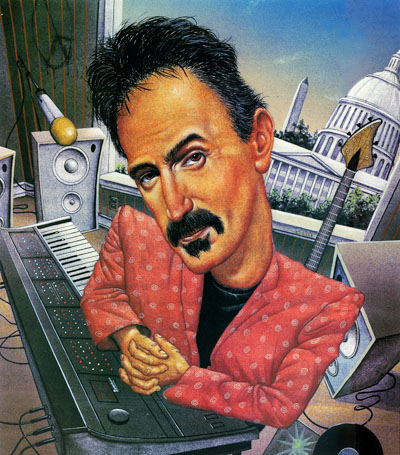

Veterans of his keyboard chair recall the life & work of Frank Zappa

At age 52, rock stars are typically shunted onto gondolas and shoved across the Styx toward an afterlife of oldies tours and appearances with Peter Noone on VH-1. Meanwhile, politicians, at that same age, keep busy casting furtive glances toward Pennsylvania Avenue, while classical composers savor one last season of critical characterization as "young." Fifty-two is young, old, the prime of life, a plateau, a time for autumnal reflection or a brisk second wind. All you can say for sure about 52 is that ifs too soon to check out. Yet that's just what Frank Zappa did. On the evening of Dec. 4,1993, the rock innovator (not a star, exactly), political commentator (certainly not a politician, or anything nearly as tawdry), and composer (see below) succumbed after three years of battling prostate cancer. Or, as the Zappa family put it in an official statement released the following day, "Frank Zappa [has] left for his final tour."

Of all the hats worn by Zappa, the one marked "composer" is probably most appropriate. Yet it's a difficult fit. Just what kind of a composer was he? He didn't study music "formally," which means that he didn't chain himself to a desk for years and submit to lectures on how to avoid parallel fifths. For better or worse, he learned the trade on his own. This process, and the results it would yield, mark Zappa as arguably the most important composer of our time.

An extravagant claim? Consider this: The twentieth century is all about meltdown. Empires collapse into mobs of liberated people, who quickly get busy slaughtering each other or their neighbors. The church, or what's left of it, scrambles to salvage its pre-Renaissance authority as its wise men puzzle out new notions of morality and relevance. And music, once the plaything of a priesthood of pedagogues and virtuosi, is ripped from the bosom of the conservatory and attacked by ... blues singers! Cowboy yodelers! Spiky-haired nihilists! The barbarians clamor at the gates, armed with guitars, and not one of them has ever played a C major scale with correct fingering.

Mass media levelled the barriers between art music and folk music. By the time discs by Enrico Caruso and Louis Armstrong started selling side by side, the war was already over. Ever since then, the old guard, the keepers of the flickering flame, have been ducking and weaving, growing long sideburns, conducting concertos for orchestra and rock band, composing noisy masses based on equal parts Ralestrina and Presley. Most of the time, they weren't fooling anybody. Their time was up, and all their desperate choreography was only a tap dance to Gotterdammerung.

Irreverence has been the most effective catalyst in the democratization of music. Those who understood the old ways well enough to ridicule them were tradition's most dangerous foes. Erik Satie was the first; by composing a 52-beat piece for piano and directing that it be repeated 840 times over a 24-hour period, he reduced the profundities of composition to the idiocy of babble. Decades later, John Cage made the point through silent pieces, which elevated random sound – a cough in the audience, an airplane flying by – above music itself in the hierarchy of performance.

Frank Zappa is third and final totem in this pole. By coming at music not from academic roots, as Satie and Cage had done, but from R&B bands with names like the Omens, The Blackouts, and Captain Glasspack And His Magic Mufflers, he demonstrated that "formal training" was no longer essential, even among those who would call themselves, in the old sense, artists. He represents the triumph – or, possibly, the civilizing – of the barbarian/artist.

Purely on the technical level, his accomplishments astonish. He started playing drums at the age of 12, and switched to guitar at 18. Two years later, in 1960, he scored a B flick, The World's Greatest Sinner, a follow-up soundtrack, to Run Home Slow in 1963, helped him set up his own recording studio in Cucamonga. Much of what he played in those days was based on doo-wop R&B; he even co-authored a modest hit, with Ray Collins, for the Penguins, titled "Memories Of El Monte." One of his R&B bands, The Soul Giants, eventually mutated into The Mothers and began stretching out in strange directions. Their debut album, Freak Out!, was released in mid-1966 and, in the alarmed words of hippie rock journalist Lillian Roxon, "grew on the public like an evil fungus"; the seeds of acerbic commentary and musical experimentation were already sprouting on "The Return Of The Son Of Monster Magnet," "Help, I'm A Rock," and other cuts from this double LP.

Even in those early days, Zappa stalked the orchestral format. His first solo album, Lumpy Gravy, featured a 50-piece ensemble that included 19 string players. Later, he alternated between largely instrumental albums, such as Hot Rats and Just Another Band From L.A., ground-breaking multimedia projects (200 Motels), and sardonic vocal performances that, as if in defiance of logic and gravity, occasionally floated toward the top of the charts ("Dancin' Fool," "Valley Girl").

More and more, however, "serious" orchestral composition became a central part of Zappa's output. Zubin Mehta and the L.A. Philharmonic premiered his score to 200 Motels in 1970. More ambitious large-scale pieces were featured in his concert film Baby Snakes in 1981. The London Philharmonic performed a program of his music in 1983. Pierre Boulez conducted the premiere of Zappa's The Perfect Stranger in Paris the following year. Zappa himself began making guest conductor appearances in the '80s, and gave the keynote address at the American Society of University Composers convention in 1984. He assembled a massive Synclavier system and used it to write works of bedeviling complexity. His most recent release, a nearly posthumous concert document titled The Yellow Shark, deposits him square on the pedestal of respectability. Aside from an occasional trombone fart or politico-slapstick libretto, this could be mistaken for contemporary art music at its finest.

As the next century looms, the danger grows that a critical aspect of Zappa's work will be misunderstood – namely, that while textbook education may lose relevance in the postmodern era, hard work is as essential as ever. Aside from one six-month theory class at Chaffey College in Alta Loma, California, Zappa had no old-fashioned music training. Yet according to those who knew and worked with him, few people have ever put so much effort into mastering a discipline. In a world teeming with fraudulent "conceptual artists," Zappa was an anomaly – an exhaustive perfectionist, an obsessive grind, driven, perhaps, by intimations of his own mortality to demand the maximum from himself and his associates.

The Zappa story has been thoroughly documented, and will be reviewed in detail in Absolutely Frank, a collection of interviews and relevant material culled from the pages of Guitar Player and Keyboard; publication is scheduled for March 22. Until then, we may ponder his legacy through the recollections of assorted keyboardists whose own impressive careers were launched through association with this singular and significant artist.

Ian Underwood with Zappa 1967–73

I had graduated from the master's program in composition from the University of California at Berkeley. Then I was in New York, unemployed. I happened to drop by the Mothers performance at the Garrick Theater. I had never heard of the Mothers; this was the first time I had any exposure to them at all. But they were doing just the kind of thing I was interested in. It wasn't just classical, it wasn't just jazz. And there was a lot of humor. In those days, [singer] Ray Collins and Motorhead Jim Sherwood, saxophonist] were doing a lot of interplay. They had their own routines, which were mostly made up at the time.

I hadn't really hit on any work at that point, so I simply went up after the show, told Frank that I liked it very much, and wondered if I could play with them. Frank said he was interested. He asked me to come up to the recording studio, which was in midtown on the west side. I did, and Frank hired me because I could play keyboards and woodwinds, and I could read. At that point, nobody in the band was an accomplished reader, although [saxophonist] Bunk Gardner could read. But I was able to let Frank hear the notes he wanted to hear. Plus I had a background in jazz, so I could improvise. So I fit in.

My main interest was Frank's music. I was really drawn to it, it was so involving. We never did shows that duplicated records or other gigs. Originally it was almost free-form; you never knew what was going to come up. Then, just after I joined and we started touring Europe, we began getting larger audiences. This meant that they couldn't be as close to us, so the kinds of off-the-wall things that would be easy to get into at the Garrick Theater really wouldn't work anymore. You couldn't do something free-form that might not work when you've got a lot of people who have paid money to listen to you. So, more and more, a balance was struck in favor of being more organized, based on doing things that were more likely to work consistently well. Then, if other free things came along in the middle of those pieces, that would be okay too.

This didn't drastically change the way we worked, but we did start having more music to rehearse. Sometimes there would be different arrangements of tunes that the Mothers had done earlier. Then there were new, classically-oriented pieces that Frank would bring in. They were pretty complicated, but they weren't different in kind from what we had done before. There was more of a difference in scale and amount, because Frank always loved to write this way.

I didn't have any keyboards of my own when I joined the band. Don Preston was playing Rhodes and Minimoog, so we would spell each other on those. I think we also got a Kalamazoo organ, which I played onstage and on the recordings. During the last period of time when I was with him, I was actually playing woodwinds more than anything else, but before that I played a lot on Hammond organ and ARP 2600. We never really used the synthesizer that extensively, though. It was either just for solos or to play a given line that could have been done on clarinet or something else, so whatever sound we used on it wasn't a big issue. In fact, I never thought about keyboard sounds at all.

Frank worked a lot on the road. He never liked to hang out at all, because his mind was always busy thinking about something. He was constantly writing music, busy with this or that. Some people are always amazed to hear that he didn't indulge in drugs, but he didn't, except for cigarettes and coffee.

I don't think that playing with Frank helped me in any specific professional way. It didn't improve my technique. What happened, what happens to everybody in an interesting and challenging situation, is that I grew. When I joined the band, I knew nothing about '50s music. But because I had a classical background, I was already aware of all the other things that Frank was doing. I knew Varèse, Bartok, Stravinsky, and all that music; it wasn't new to me.

Ian Underwood now makes his living playing keyboards on film soundtracks in LA.

George Duke with Zappa 1970–75

The first time I met Frank was when he produced the King Kong session for [violinist] Jean-Luc Ponty. I was working with Jean-Luc at a club in L.A. called Thee Experience, and he insisted that he didn't want to do the record unless I came along with it. He didn't know Frank at that time, so he wanted somebody from his camp to be there. So I did the date, Frank liked me, and it went from there.

Maybe two months later, I was at my mother's house in Marin City, and one Sunday afternoon I got a call from Frank. He asked me to come down and be a part of this show he was doing at UCLA with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta, and the Mothers Of Invention. After that, Frank asked me to join the band. I couldn't understand why he wanted me, because I was such a straight-laced jazz player. But he liked me because I was crazy. I would do anything on the piano.

It's funny. The music we did with Jean-Luc Ponty on that record, and the stuff we did with Zubin Mehta, was advanced for the time; it's probably still advanced for now. But when I joined the Mothers, the first stuff we did was that kind of rock and roll where you do those doo-wop triplets. I was like, "Oh, God! I can't do this!" After that, of course, we moved right into the more advanced music.

Rehearsals were grueling, very tough. You would go into the studio at noon or one o'clock and be there until seven or eight o'clock in the morning. The whole band would be sitting around, and I'd be there with my keyboards. When he needed me, he called me in. When he didn't need me, I'd go out and watch television. Or Ian Underwood and I would script out who was gonna do what sound, who had the time to do this funny lick Frank wanted and then get back around the keyboard to change the patch and make the next move. See, we're not talking about synthesizers that had presets. You had to change each patch. And if you didn't get it, Frank would know it. He would look around at you and make you do it again. Onstage! It was almost like a Broadway show.

He would make us go over one lick until there was no way we could forget it. It's amazing to me to go back and listen to the tapes of what we were doing onstage. God, the amount of music you had to play the same each night! That was some of the most difficult music I've ever played, partly because he composed a lot of it from the guitar. But once I was in the band for four years or whatever, it came to a point where he didn't have to write anything out for me. I knew what Frank was looking for, and I could easily come up with parts I knew he would like. If he wanted something special, he'd just say, "We need something weird here." We'd try things until we found something he liked. We used to spend hours and hours in the studio doing that stuff.

Frank's music was like organized chaos. That's exactly what it was. Once we got to the level we were at on The Roxy and Elsewhere, there was almost nothing we couldn't do. If he wanted to move into contemporary orchestral or classical music, we could do that. If it was back to the '50s or forward into weird stuff, we could do that too. We were like a rubber-band band: He would do certain moves with his hands, and we absolutely knew what he wanted.

The only thing that made me want to retreat back to the jazz world was 200 Motels. I was still really straight then. I didn't have a big sense of humor. Even now, 200 Motels is the weirdest thing I've ever done in my life. It was so strange, I almost can't explain it. It was just very weird to be a straight-laced, thin-black-tie-wearing cat, with all these grungy hippies, for lack of a better word. But I loved it, because I knew I had something to learn, and these guys were incredible musicians. And Frank did bring out my sense of humor. By the time I started playing with Billy Cobham in '76, I was crazy. I had all these crazy statues and heads around the keyboards. That was a holdover from Frank, because I felt that this fusion music was too serious. It needed some comedy. Nobody was smiling. So Frank's attitude seriously affected me.

Frank was the hardest worker I've ever played with, hands-down. I never saw anyone work harder than he did. From the time he got up to the time he went to bed, he was thinking music. He wasn't very personable in terms of dealing with people. On a certain level, he had a problem in dealing with his musicians. Once you were out of his concept of making music, you were out of his life, and he didn't have time for you. But he was always great with me. He was a teacher: If I needed to know something, he would tell me. I know he wasn't like that with some other people. For sure, out of all the people who worked with him, I'm the one guy who never had any problem with him about nothin'. And, for the time, he paid me more money than I could have gotten anywhere else.

The only change I saw in Frank over those years was that he went from being funny/sarcastic to being almost serious/sarcastic. Toward the latter part of the time I was in the band, his sense of humor became kind of vindictive.

I last saw Frank about a year ago. He kept trying to get me to come up and do some stuff with him at his house, but I was involved with doing a lot of records. I had my own career going. I didn't really have time to be a part of Frank's world at that point. I kept planning to go up and see him, but I just never did. It's a drag.

George Duke is currently working on his next solo release for Warner Bros. Recent projects include production work for Johnny Gill and Anita Baker, music direction for Comic Relief, incidental music for assorted children's television shows, and The Muir Woods Suite, an album of original orchestral music.

Patrick O'Hearn with Zappa 1976–78

I got the gig with Zappa as a result of my friendship with Terry Bozzio, his drummer at the time. Frank had just let everybody in his band go, except for Terry, and he was looking to start again. I was in Los Angeles, playing a jazz gig with [saxophonist] Joe Henderson. Terry asked if I wanted to stop by the old Record Plant on Third Street after the gig and listen to some things they had recorded. I said, "Sure."

I stopped by at about 2:30 in the morning. Not being one to leave my upright bass in the car, I carted it into the studio. Frank, upon seeing me with this bass, remarked, "Do you play that dog house, fella?" I said, "Sure do." Then, without even a formal introduction, he said, "Well, how would you like to put some acoustic bass on this track?" I said, "Let's do it." So the engineer strung up a couple of microphones, I did finally shake Frank's hand, then I went out into the studio. He rolled the tape, and I played. The cut was finally released as "The Ocean Is The Ultimate Solution," on an album called Naval Aviation.

Frank seemed to like what I played. He asked if I played electric bass. I said, "Sure." He then gave me a cassette of a piece he and Terry were working on. It was typical of Frank: From a variety of live performances, he had assembled a rhythm track of Terry's drumming at different tempos. He was an absolute master of two-track splicing, a wizard with a razor blade, before he got his Synclavier. It was an interesting piece, with all sorts of rhythm and tempo changes. He said, "See what you can do with this tomorrow night."

So, being a huge fan of Frank's, I stayed up all night and designed a road map of this piece, which hunted and skipped all over the place, with wild meter changes. Then, the next night, I came back in from the gig with Joe and slapped on the electric bass part. He came into the control room after I played down a pass, and he said, "Well, would you like a job?" I said, "Sure." He stuck out his hand and said, "You've got a job."

I really lucked out in the way I came to join Frank's band. In the following years, we held auditions for different positions in the group, and they were brutal. It was like the scene in that terrific Mel Brooks film, The Producers, where they say, "Okay, all the dancing Hitlers, please wait in the hall!" Someone would play a few bars, then Frank would interrupt: "Next." I'm glad I didn't have to go through that, especially since I can't sight-read worth a darn. But Frank was very generous about that. He would play on the strengths of his players, so I could take the charts home and figure them out on my own.

The toughest chart I ever had to play with Frank was the straight version of "The Black Page." It's mainly difficult for the drum chair, but it's a tough chart all around. We actually worked up two arrangements of it: the straight one and the disco arrangement, which was hilarious. Terry would slip into sort of a Latin hustle beat, and I did the ubiquitous bass octaves that had been made popular by God knows how many groups of the era. We'd hold a dance contest onstage; some of that is in the concert film, Baby Snakes. He would bring up members of the audience and have them dance to this arrangement. Peter Wolf and Tommy Mars would play the keyboard chart as written, but Adrian Belew, Terry, and I would slip back and forth between the disco and straight arrangements, causing these hiccups.

Anything went. I remember writing down a story that had occurred to me, part of it personal and part of it fiction. I read it to Frank before one show, and he said, "Let's do this tonight!" Sure enough, at one point in the show, they improvised musical background, and I recited the story.

At one point, Frank, Terry, and I were just a trio. We jammed and played throughout the summer as such. Frank was producing a Grand Funk Railroad album at the time [Good Singing Good Playing, and those guys would come in and encourage Frank to "revive the power trio." This was before the Police; the last trios had been Hendrix and Cream. We thought about that and actually rehearsed it for a while. But eventually Frank felt that he needed at least five guys to make things interesting.

Frank had this wonderful open-door policy. You could always go up to his place, provided he wasn't locked into his studio and not to be disturbed, hang out, play, or listen to what he was working on. He was enthusiastic about sharing thoughts, ideas, or technological tips. That's actually how I got into synthesizers. In '76 and '77, not only were these instruments not widely available, they were terribly expensive. The Oberheim Four-Voice was a $5,000 proposition, and that's in 1976 dollars. But Frank could afford to purchase these new instruments, and he always encouraged me to fool with them. He would let me borrow stuff, like his ARP 2600, and take it home. Or I could go into another room in his studio and play with the tremendous E-mu modular system he had. He also had all this outboard gear, an enormous collection of pedals and gadgets; I was free to sift through them, pull something out, and try it. Anything that wasn't on-line in the studio was open to be fiddled with. That whetted my appetite big-time.

All these legends and mythologies surrounded Frank – things he had supposedly said or done. It was all a bunch of nonsense. Perhaps a certain amount of this came from outrageous actions by members of his band. As Frank once said to me, "I seem to bring out the Barnum & Bailey in my musicians." That was true. I remember going to see Frank's band in the early '70s, when Flo and Eddie (singers Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan) were with him. It was a smokin' band. Frank ran the show, conducted, and whatnot. But it was the band, not Frank, that did all the flamboyant and theatrical stuff.

I last saw Frank on March 20, 1992. He had 25 or 30 people up for dinner, including some musicians I hadn't seen for a while. Most of them were like his former students, people who had worked with him, and he was really curious about what was going on with them. It was a good time to see Frank. He had been sick, but he was in good shape that night, and quite animated. He was putting together You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore, so he was demonstrating his incredible prowess with editing on his hard disk system. He had assembled something that sounded like a single performance but was actually taken from different bands over a period of probably 15 years, then cut and pasted together.

I got a chance to talk with Frank that night. He was excited that I was working in film, and he gave me tips about working with foreign orchestras. He talked to me about working with classical musicians in general. Specifically, he recommended the orchestra in Budapest.

His oldest boy, Dweezil, was playing some tapes of things he had done recently. I looked at Frank as he was watching Dweezil, and I saw that look of pride in his face. Being a father myself, I recognized and understood that. There it was, that unspoken idea that life is such an interesting mystery.

The man was an extremely important influence in my career, and continues to be to this day. At least once every week in my life, a situation arises that calls for a verse or a chorus refrain from one of Frank's lyrics. Whenever I'm aggravated about something, or some ironic incident occurs, a line from his material comes to mind, and I just start laughing. My children all know what's going on: "What is it, dad? What Zappa song is it from this time?"

Patrick O'Hearn is simultaneously recording a new album, upgrading his studio, and poring through editor/librarian manuals. "I'm swamped with technology," he reports. "I could give you a lot of parameters for a lot of different devices, but whether I should be allowed to drive a car at this point is certainly open to question.

Peter Wolf with Zappa 1976–80

I was in Los Angeles literally just two weeks when Frank Zappa called me. I did a job with Lalomie Washburn, a singer who was renting a room from Andre Lewis, the keyboard player who replaced George Duke in Frank's band. She played Andre some of the tapes, and he went to Frank's house to tell him about me. At that point, Frank was looking for a new keyboard player; he had auditioned, like, 60 of them. So he called me: "Hi, this is Frank Zappa. I'm looking for a keyboard player. Do you want to audition?" I said, "Sure!"

I went over to his place and went through the whole madness of reading "The Black Page." It was so hard! I can read anything that a studio gig in L.A. would ask me to read, but Frank Zappa material was beyond belief: seventeen tuplets followed by sixteenth-notes, and that's followed by quarter-note triplets. Nobody in the world can sight-read that correctly. So I would trip over these incredible rhythms, and he would go, "No, that's wrong. Try it again."

After a while, Patrick O'Hearn came in; he had already been in the band for a year. Frank said, "Patrick, why don't you play with this guy?" Patrick had his acoustic bass, so I played piano. We had a great time, because we were both jazz players. We were flying! Then Frank said, "You like to play with this guy?" Patrick said, "Yeah!" And that was that.

Frank put musicians through this ordeal because he liked to make them humble. He even did that to Jean-Luc Ponty! He looked him in the face and said, "So you can't play that, eh?" You have to say, "I guess not, Frank!" I said to him once, "Why don't you play this?" He laughed and said, "I can't play that! I have to make a living for all of us by writing it."

He rehearsed us to death. I've never rehearsed that way in my life, before or since. First, he would lay all this music on you, which was a conglomerate of styles: '50s rock and roll, punk rock, new wave, jazz, Béla Bartók, Greek folk music, and weird 12-tone stuff. You had to put on all these different hats, and be quick and spontaneous about it. I had to get up in the morning, 'shed like a motherfucker to get the music down, then go to rehearsal at 11 o'clock. The band would practice all this crazy stuff, just trying to read it and play it together. At four or five in the afternoon, Frank would come in, and he'd stay with us until two or three in the morning. He would pick a song, we'd start on it, and he would constantly change the parts: "No, do this. Play these notes. You, do this rhythm." Then, all of a sudden, he would stop, and we would go to another song. A minute and a half later, we would come back to the first song, and he expected everybody to remember every detail. Obviously, nobody could. But he did. The guy had a memory beyond belief.

Frank was the most intelligent human being I've ever met. On top of that, he had an incredible sense of humor. That, together with the intelligence, brought out the witty commentary of the times in his music – funny lyrics and funny music that still had great grooves. He utilized all musical possibilities, but he never looked at the charts. He never wrote a note thinking, "I could have a hit with this." That was the last thing on his mind.

I knew that Frank had cancer, but I couldn't call and say, "Hey, Frank. I heard you have cancer." It was a strange situation, because I respect people's privacy. Besides, even though my wife and I got closer to him on a human level than anyone else I've ever seen, except for maybe his early guys, Frank didn't really have friends. He didn't want friends. Knowing him, I thought he definitely wouldn't want to talk about the disease, and it would have felt weird if I had called him all of a sudden. So I didn't call him.

Then, one day, he called me and left a message: "Hi, this is Frank Zappa. Call me." My wife said to me, "That's a bad sign. He wants to see all his buddies for the last time." I felt so shitty that I called him right away: "Frank, name the time. I'll be there." Now, when I was with Frank, he was always into good wine, so I took a bottle along. I got there at five or six in the afternoon, and we were hanging until four in the morning. He looked remarkably good. It was like nothing had changed, like we were just off the road.

Frank mastered one of the greatest things that anybody can master in life: He treated all human beings equally. Regardless of whether you were a homeless person or the president, he would honestly, from the depths of his heart, approach you from the same starting position. There wasn't any, "Oh, my God, it's the president of the United States!" He could[n't] care less about that, or about how much money you had. I called him on this once. I said, "You know, you're quite a character, because you treat people equally." He laughed and said, "Yeah. Everybody is an asshole until proven differently."

Peter Wolf maintains a hectic schedule of production in L.A. Recent clients include the Pointer Sisters, Chicago, and Indecent Obsession. He is also working on his debut solo album, tentatively scheduled for release in July on the Angel label.

Tommy Mars with Zappa 1979–C. '93

I had been earning a living in Santa Barbara as a choir master, organist, and solo jazz pianist when my friend Ed Mann, who was playing percussion with Frank, called and said that Frank Zappa was auditioning keyboard players. Aside from "King Kong" and "Peaches En Regalia" I didn't really know Frank's music. I just thought he was kind of a nutty guy. But he called me up, and I went down to his house.

Immediately, Frank puts me to the wall. He was still writing "Sinister Footwear," although it was called "Slowly" at the time. The ink was still wet on it. He said, "I want to hear how this sounds." I hadn't seen these kinds of rhythmic relationships since I was doing serious contemporary classical music in college. I read through it; it wasn't perfect, but at least I started and stopped at the right time, and that's reading to me. Then he played a couple of measures for me and said, "Okay, this is Section A. Here's Section B. Now play them A-B-B." Then he said, "Here's Section C. I want you to put A with C, then do two of B ..." I couldn't write any of this down, because he wanted to check my memory. It was baffling, with these strange guitar licks. I have perfect pitch, so that helped a bit, but I was like, "Holy shit! This guy is stretching me like freakin' gum!"

Then he said, "Hey, can you sing?" I said, "Look, man. I sing for my supper. I have to sing every night on these club gigs. I must know a thousand songs. But my head is so fucked up from this audition that I don't think I could remember the lyrics to one song all the way through. How about if I just improvise for you?" He gave me the strangest look, and he said, "Man, that's the first right thing you've done all day. Go for it, kid."

So I started wailing. For some reason, the last thing I did was that song from The Wizard of Oz, the one that goes, "Bzz bzz bzz, chirp chirp chirp, and a couple of la-de-dahs." I don't think I'd ever done that song before, but I played the most wild, insane version. And he totally broke up. He said, "Number one, just sit right where you are. Number two, I don't think you're ever going to play again in any more Holiday Inns. Number three, I'm gonna go up and get my wife; I've never heard anything like this before. Just hold tight." And he went upstairs.

While he was gone – I can't tell you how cosmic this was – I looked at some of the music he had in the room. And on the bottom of one sheet, it said, "Munchkin Music." I said, "Whoa! I think this is meant to be."

He came back with Gail and said, "I want you to do it again, exactly like you just did it." I said, "Look, man, that was an improv. But I can approximate it." I went for it, and Gail just fell in love with me. So Frank gave me 12 or 13 pieces and said, "I want you to learn this. I'm putting you on a temporary retainer." Back in Santa Barbara, as I went through this stuff, I was thinking, "My God, this is very Hindemithian," or, "These melodic ideas and rhythmic phrases are incredibly Stravinsky-like." It was barking at all the composers, yet it didn't sound like them. It was strictly Zappa's own hybrid. I noticed his passion for reiterated notes. To me, if you play one note, you've said it. But he always had to play the same note two or three times. That was a definite rhythmic characteristic.

A week later, I came back down from Santa Barbara; I had learned every piece that he gave me as a solo piano arrangement, even "The Black Page" and "Punky's Whips" He thought I would just learn the chords and some of the melodic licks, but I did everything as if I would do it solo. So he was utterly flabbergasted. The rest is history.

The main thing I can say about Frank's music is that it is perfectly authentic. Whatever part of the musical encyclopedia he chose to use, it was completely as it should be. I was trained with him not to overstep a style, because that was the shock factor.

Everything was so pure and organic, no matter what style. Since everything was so authentic, it made complete sense that all of these varied styles work together. In "Baby Snakes" for example, he would expect me to crush the A-Bb in this lick going up to the fourth, B to E. It was just a doo-wop tune when he started it. But since the piece as a whole was sort of a mini-opera, with so many sections, I put a parallel line a sixth below that figure. If all of "Baby Snakes" was just in the one style, I would never have put those sixths there. But since it had so many styles within it, I took the chance, and Frank said, "That's exactly what I want!"

Frank loved to test the band members. I'll never forget one tour. We were getting ready to go to England. Then, three days before we went out, Frank came to rehearsal and said, "I want every piece in this show to be done reggae. I don't care if we stay here until the tour starts, that's what we're gonna do." So we burned out that night, we burned out the next day. Then, the night before the tour, he comes back all happy and says, "We're not gonna do that reggae anymore." I mean, he put us right in front the muzzle of the gun, man! And it was such a high! No one stretches you like that. Just think of the incredible shuffling of the deck you'd have to do in your mind. And we'd always see how fast we could do it. You left that experience feeling that no one could touch you. You could do anything.

He was extremely difficult sometimes. He knew exactly what button to push. I saw people who revered him so much, who were very chopsy but who didn't have exactly what he needed, absolutely cremated on the spot by him, in rehearsals, in auditions, onstage. I think that was because Frank liked to test boundaries. He pushed every boundary personally, sociologically, politically, comedically, and tragedically. He couldn't be happy until it was ready to break.

I have a story to tell you in that area. One day, we were working on the Mothers of Prevention album. We had been in the studio for probably 35 hours, and we were listening to a playback. Dweezil came in, wearing his baseball gear; he was playing for some Valley Little League team. He said, "Hey, Frank. I just pitched a no-hitter." He was all hopped up, and I was grooving on it. But Frank didn't look at him for a second. He didn't even interrupt his statement to me; he was telling me to go in and double a part or something. That hit me like a hatchet in my heart. I thought, "Why, you son of a bitch! You bastard! You didn't even say hi to your kid. Nice job, good for you." But Dweezil just went on his merry way; it didn't look like he was hurt or anything.

Then, about two hours later, we're back in the booth, listening to a playback and having a hamburger. Dweezil came in to get something. Frank came up, put his arm around him, pulled him close, and said, "Nice going, slugger. I'm really proud of you." It made me almost cry to see that he was a real family man. He was just very lean with compliments. He hardly ever said, "Really good job." But when they did come, they'd just warm you right up. That's one thing I love about Frank.

I called Frank a few months before his death, when he had taken a little turn for the worse. He was talking to me about the Ensemble Modern and The Yellow Shark. It was really hard for me to visit him; it's tough to see someone you love so much being debilitated. Frank spent a lot of time during that visit encouraging me to go out and do my own thing. I sometimes have a problem with that, because it's hard to be a bandleader. But he stressed to me, "You're never gonna be happy unless you do it."

I said, "Frank, how am I gonna pay for musicians to help me?" He said, "Tommy, do like I do. Hire the handicapped." That made so much sense to me: You get somebody who's young, who's hungry. You don't have to get the yo-cats. That cemented it in my head that this is what I've got to do, and I'm making strides in that area now.

I truly believe that Frank will be remembered as the Bach of this century. He took what was before, assimilated all the elements, and made it new. He was always on the advance guard. Listen to "Brown Shoes Don't Make It": Those lyrics are current still. He was doing rap way before rap. He understood that we don't speak in regular rhythm, so in his music the lyric was always important enough to have its own rhythm. That's why there's a lot of odd time in his work. I was always impressed with how he wedded the lyric to the beat. It was always easy to sing his stuff, because it was so easy and normal to say.

The dude had the kind of vision that only a few people get to have. His stuff had so much drama going on. He wedded so many areas of culture. But the best thing I can say about Frank is that as tortured as he was, he had the ultimate sense of humor. He challenged us to laugh at ourselves.

Tommy Mars recently finished recording and touring with Mona Lisa Overdrive. He is now working on his first solo album for Stone Records.'