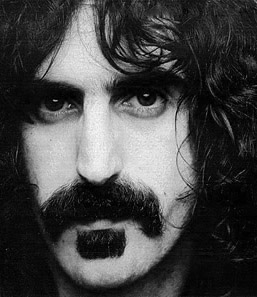

Lucky? Sure. Nice? Never. Not Zappa.

Lucky? Sure

Nice? Never

Not Zappa

Toronto Observer(?)

By Peter Goddard, staff writer

Consider the man who fostered a generation of rock radicals

Considering the boomer gloom now settling down because of the loss of Frank Zappa – rock's greatest critic, who died of prostate cancer Saturday at 52 – you've got to see one bright spot: he was a pretty lucky guy.

Yes, lucky.

Sure, the recording industry lumped him in with Pia Zadora and Tiny Tim in the who'll-buy-this-stuff? category. "Bizarre," as one obituary put it with some finality.

But listen: The recording industry never did care for someone who, as the oldest son of that good Catholic couple, Francis Vincent and Rose Marie Zappa, had little reason to take it seriously. Someone who'd made fun of it and out-flanked it at every turn (at the height of blissed-out Beatlemania he released, We're Only In It For The Money).

So why lucky?

Consider his background.

For Once A Catholic, a collection of stories, he remembered the impression left with him by his grandmother's funeral: "The choir was singing, and I could see from the way the candle flames were wavering that they were responding to the soundwaves coming from the choir. That was when I realized that sound, music, had a physical presence and that it could move the air around."

His first influence was Spike Jones

Lucky? Dad, a metallurgist/ineteorologist studying poison gasses, brought home gas masks to hang on the wall. It was the 1950s. Young Frank, knowing black comedy when he lived it, went immediately into music where Spike Jones was.

Lucky? Yes,there's more. His first influence was indeed Spike Jones, the sweetly wacky bandleader who applied the Marx Brothers' techniques to popular music. Following Jones's lead, Zappa later packaged music with such titles as: Yellow Shark (his last album), Don't Eat The Yellow Snow, Orchestral Favorites and Zoot Allures. (The young Zappa had learned nothing much was sacred – except perhaps, such a non-musical matter as his family: wife Gail and his four kids. Moon Unit, 26, Dweezil, 24, Ahmet, 19, and Diva, 14, were at his bedside in Los Angeles).

Lucky? About the time he heard the blues via Slim Harpo, Howlin' Wolf or Sonny Boy Williamson, he was also listening to Varese, Webern and Stravinsky. Years later he told me – lectured would be a better word – that it was because he didn't have much musical training.

Yes, lucky.

But not nice.

As pop icons went, Frank Zappa did his best to not be nice. He started out, he once said, in the belief that the music business was "Dada."

But later on, he concluded, "the music business is people who make endorsements for liquids with bubbles in them."

They were out to pervert rock 'n' roll

His very history in the annals of pop is a study in not being nice. He called the band the Mothers, and they were out to pervert rock 'n' roll. A terrified MGM executive forced the change of name to Mothers Of Invention. Zappa's revenge was to release, in 1966, Freak Out!, rock's first double-LP and its first – gasp! – "concept LP", ahead of the sacrosanct Beatles by a full year.

A Mothers' concert was a challenge. Zappa's attraction extended to the extreme ends of rock's spectrum: from the metal head cases who thought he was tough, to rock's intellectuals, who kept hearing stuff like tone rows and classical quotations in his music.

He fostered an entire generation of rock radicals: The Tubes, The Residents, Arthur Brown, Alice Cooper among them.

Not nice, as always. His problem was his intelligence. In an area of artistic activity, he always counted more on one's talent than on one's ability to whip out a credit card or something closer to the front of the belt.

And he hated critics, mainly, I came to believe, because they thought they knew what he was about when they so obviously (to him) didn't.

"You need to know four things to understand my music," he informed me loftily, one afternoon. "You have to know plenty about rhythm 'n' blues. You have to have a working knowledge of all Western art music for the past 100 years. You have to have a complete working knowledge of all my LPs since 1964. And you have to have seen at least one of my shows at least once a year."

"Hey, babe," I was going to say, "no probs."

But he glared as if he didn't want to believe. I could never be as lucky as he was.