Difference between revisions of "Maverick"

Propellerkuh (talk | contribs) m |

|||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

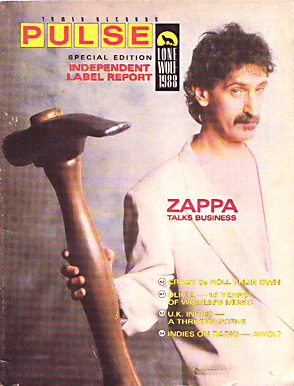

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Pulse_Indie_Special.jpg|frame|]] |

| − | Most people know [[Frank Zappa]] from his recordings with the [[The Mothers|Mothers of Invention]]. But he's also an astute businessman who refuses to walk the party line. | + | Most people know [[Biography|Frank Zappa]] from his recordings with the [[The Mothers|Mothers of Invention]]. But he's also an astute businessman who refuses to walk the party line. |

| − | In one respect, Frank Zappa shouldn't be featured in this special independent label issue. His label, [[Barking Pumpkin]], is pressed and distributed by Capitol/EMI-Manhattan/Angel, a major record distributor. | + | In one respect, Frank Zappa shouldn't be featured in this special independent label issue. His label, [[Barking Pumpkin Records|Barking Pumpkin]], is pressed and distributed by Capitol/EMI-Manhattan/Angel, a major record distributor. |

| − | But Zappa also releases music through independent distribution channels. He may be the only major artist who owns his catalog (which is approaching 50 titles); many of those titles are available on compact disc from ''[[ | + | But Zappa also releases music through independent distribution channels. He may be the only major artist who owns his catalog (which is approaching 50 titles); many of those titles are available on compact disc from ''[[Rykodisc|Ryko]]'', the Salem, Mass.-based audiophile label. |

''Ryko'' recently released the first of a projected six-volume, double-CD (each) set of live Zappa recordings titled [[You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore]]; the second and third volumes are due by year's end. Ryko has also released selected Mothers of Invention and Zappa catalog on CD, and three more titles – [[Baby Snakes]], [[Waka/Jawaka]] and [[One Size Fits All]] – are due shortly. | ''Ryko'' recently released the first of a projected six-volume, double-CD (each) set of live Zappa recordings titled [[You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore]]; the second and third volumes are due by year's end. Ryko has also released selected Mothers of Invention and Zappa catalog on CD, and three more titles – [[Baby Snakes]], [[Waka/Jawaka]] and [[One Size Fits All]] – are due shortly. | ||

| − | Zappa's association with ''Ryko'' dates back to 1986, when ''Ryko'' chief Don Rose approached Zappa seeking a licensing deal to release Mothers and Zappa masters on CD. At the time, Zappa had a European deal with EMI, which gave that company the right to release his titles on CD. Ironically, EMI refused. | + | Zappa's association with ''Ryko'' dates back to 1986, when ''Ryko'' chief [https://www.linkedin.com/in/rosedon Don Rose] approached Zappa seeking a licensing deal to release Mothers and Zappa masters on CD. At the time, Zappa had a European deal with EMI, which gave that company the right to release his titles on CD. Ironically, EMI refused. |

Zappa's pairing with Ryko was a match, as they say, made in heaven. Zappa was one of the first rock artists to embrace digital recording technology, and Ryko has acquired a reputation in the record industry for high standards of quality and attention to detail. | Zappa's pairing with Ryko was a match, as they say, made in heaven. Zappa was one of the first rock artists to embrace digital recording technology, and Ryko has acquired a reputation in the record industry for high standards of quality and attention to detail. | ||

Frank Zappa is a maverick. He's also an astute businessman who had the foresight to get control of his master recordings, a qualified observer of the music business (having been in it for over 25 years) and a respected and active advocate for freedom of speech and artistic expression. | Frank Zappa is a maverick. He's also an astute businessman who had the foresight to get control of his master recordings, a qualified observer of the music business (having been in it for over 25 years) and a respected and active advocate for freedom of speech and artistic expression. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:PulseIndieSpecial1988.jpg|frame|© 1987 Lynn Goldsmith]] | ||

'''Do you finance all your own projects?<br> | '''Do you finance all your own projects?<br> | ||

Latest revision as of 05:55, 30 September 2021

By J.B. Griffith

Pulse! Indie Special, 1988

Most people know Frank Zappa from his recordings with the Mothers of Invention. But he's also an astute businessman who refuses to walk the party line.

In one respect, Frank Zappa shouldn't be featured in this special independent label issue. His label, Barking Pumpkin, is pressed and distributed by Capitol/EMI-Manhattan/Angel, a major record distributor.

But Zappa also releases music through independent distribution channels. He may be the only major artist who owns his catalog (which is approaching 50 titles); many of those titles are available on compact disc from Ryko, the Salem, Mass.-based audiophile label.

Ryko recently released the first of a projected six-volume, double-CD (each) set of live Zappa recordings titled You Can't Do That On Stage Anymore; the second and third volumes are due by year's end. Ryko has also released selected Mothers of Invention and Zappa catalog on CD, and three more titles – Baby Snakes, Waka/Jawaka and One Size Fits All – are due shortly.

Zappa's association with Ryko dates back to 1986, when Ryko chief Don Rose approached Zappa seeking a licensing deal to release Mothers and Zappa masters on CD. At the time, Zappa had a European deal with EMI, which gave that company the right to release his titles on CD. Ironically, EMI refused.

Zappa's pairing with Ryko was a match, as they say, made in heaven. Zappa was one of the first rock artists to embrace digital recording technology, and Ryko has acquired a reputation in the record industry for high standards of quality and attention to detail.

Frank Zappa is a maverick. He's also an astute businessman who had the foresight to get control of his master recordings, a qualified observer of the music business (having been in it for over 25 years) and a respected and active advocate for freedom of speech and artistic expression.

Do you finance all your own projects?

Right. It's the only way to avoid censorship in the United States.

Please elaborate.

If an artist is contracted to a record company, and the record company is acting as his bank, and somebody in that record company decides they don't like what his songs are about, he stands a very good chance of not having his songs reach the marketplace. As long as the marketing entity has your balls in a bear trap with the finances, you can't be truly independent. And, considering the type of stuff I'm interested in working on, it seems to be the only way for me to function.

What do you think is wrong with major labels today?

Well, I'll give you a list. First, I believe the industry was better off in the late '60s when you had all those guys with the cigars sticking out the front of their mouths who used to say "I dunno" a lot. Now, what that means is, a person might walk through the door – let's take Jimi Hendrix as an example. And certainly, this guy with the cigar sticking out of his mouth is not going to be a Jimi Hendrix fan, but he also might be smart enough to know that somebody else out there in the marketplace might like it, even if he doesn't.

The difference in the business today is, you have a bunch of people in the lower age brackets who are convinced that they do know what the public wants, and they have imposed their tastes on the public. I don't think their tastes are all that good. And the new artist who might be doing something unusual, or might be setting out in some ground-breaking direction, is pretty much squeezed out of the marketplace. So that's one problem.

The other problem is that when MTV first came along, every major record company looked at it as if it was going to be the thing that would save their lives. It was like they forgot about music and started signing models. MTV should be called "Model TV" instead of Music TV, because it has more to do with the way people look.

The mistake the record companies made when they stopped thinking about "how good is the song?" as opposed to "what does the group look like?" is that they geared up for a whole different type of merchandising: everything based on physical appearance. The problem with this type of merchandising is that there's only one game in town. There's only one MTV, and their playlist is not that long.

Whereas, if a record company had stuck to the idea of making music, you've got tens of thousands of radio stations all over the United States, any one of them capable of breaking a hit. Their odds were actually better for hits before they went pictorial. And I think they ought to re-assess their commitment to non-music and take a look at a more traditional way of marketing the stuff.

Because I believe that if you look at a video, unless you're really, truly stupid, you've seen it enough after six times. And if there's a good song and you really like it, you can listen to it hundreds of times – it becomes part of your life. Now that can still happen, and that's what builds valuable catalog; it's what gives you long-range income. It also makes hit records, too. I mean, if you can't get a song out of your head, that's a hit.

By shifting the emphasis over to pictures of guys, surrounded by models, waving their guitars in the air, I think that they've made a mistake. There's a certain part of the audience that wants to consume tunes – they want stuff they can listen to, and they don't really give a fuck about MTV, because they consume music while they're riding in their car or they consume it on the job. The amount of time that they have to watch pictures of somebody doing a song is less than the amount of time they have to be exposed to a speaker someplace. So I think that what the record companies have done has been pretty shortsighted.

And MTV has become increasingly arrogant through the years, to the point now where video producers will actually call them in advance, tell them what their storyboard is and ask permission whether certain images are OK to go on the air. What the fuck is that?

Censorship. Speaking of – what about radio? The increasing reliance on programming consultants leads to a certain amount of narrowcasting there, too. Right?

The reason radio got into consultants in the first place is because they tried to build up a layer of security to protect the license holder from charges of payola. In other words, before the days of the consultants, disc jockeys or the local programmer would be picking the material that went on the air. And there was always the possibility that that guy was gonna get a little present someplace. So it does give the license holder a certain amount of "plausible deniability," to use a Reagan Administration term. Then again, you're in a situation where one man's taste is inflicted on the nation.

Do you see any remedy?

Well, the people who might prefer to have radio and MTV behave in another way should make their wishes felt by either writing or calling. They won't, though. The ones who don't like radio and don't like MTV the way it is have stopped listening and stopped watching. They don't give a fuck.

But, broadcasting being what it is – a business – I think that it would be unwise for a man who owned a [radio] license to ignore any information that came his way from the audience. The audience has to be factored in to [the station's] decisions as to what the programming is. And if the audience doesn't speak up, then the only data that that license holder is gonna receive is gonna be from the people who watch Jimmy Swaggart, who are sitting at home right now with these cards that were printed and mailed out to them that have little things that they can fill out about how they can complain about what goes on TV and radio.

That's real. Many television evangelists provide – sometimes at a nominal fee – packets of cards. All you have to do is sit there and fill out the name of the show, what time the "naughty" word or whatever it is that offended you went on the air and the name of the person who said it, and you've got thousands of people all over the country with nothing better to do than to fill these cards out and send them to the FCC.

And the FCC then turns around and threatens the license holder. The license holder – who's got several million bucks invested in his license – goes, "Well, fuck, I didn't want to play that record anyway," and he takes it off. So there's another example of a narrow viewpoint controlling what the rest of the population gets to see and hear.

If you look at the statistics, there's 50,000 new songs recorded every year. Did you know that? That means that if 50,000 got recorded, how many got written? Think of all the people who didn't even have a record contract, OK? Now, out of the 50,000 that got recorded, how many of 'em got to be hits? 20? 30? Does that mean that every other song written in America during that year was a piece of shit?

We both know the answer to that one.

I know, but that's the point. Things can't be that bad in the creative community that we must be subjected to hearing the same 20 songs over and over again for a year on end. I think there's room for diversity here. But one of the reasons why the record companies don't opt for diversity is they have a merchandising theory that goes something like this: If a year produces one major blockbuster hit – and it's a record that everybody must have, like Thriller or something like that – then the stream of customers who goes into the store to pick up Thriller stands a good chance of picking up something else while they're in there. So [the labels] don't care what it is that gets to be the big hit, but they want one every year.

You'll notice that every year somebody sweeps up all the awards on the Grammies. And [the labels] manufacture these artificial phenomenons in order to just increase the foot traffic in the stores. This is a merchandising theory that the majors have to sell all the rest of their major catalog.

There certainly are a lot of records released that fill that bill.

I think it's fine that there are; I think that everybody's musical tastes ought to be catered to. I think that if you want to listen to Whitney Houston, you need to have it. You should have as much as you want. And the same goes for Michael Jackson or whatever the fuck it is, you know? It's there for you to enjoy.

But what about the people who don't want Whitney Houston, and don't want Thriller? What about the people who are actually repulsed by the stuff that goes on the radio? They've got dollars to spend, too.

There are a lot of them.

That's the reason why we have independent labels. Because that's the only way that the tastes of that part of the audience are going to be serviced.

What prompted you to get control of your catalog?

I believe that it's a viable catalog that will continue to sell for years and years and years. You don't have to be a genius to realize that this is some of the most pirated and bootlegged material that has ever been put on the market. I've got three albums that I picked up while I was in Europe that are counterfeit versions of things from my catalog. And the amount of bootlegs – cassette recordings done at concerts and stuff like that – of my material is staggering. There are more bootlegs out than real albums. Maybe a hundred different titles – one of them is a 10-record box and another one is a 20-record box. So there is an audience for this stuff; the biggest problem that I have in dealing with that audience is just getting the product to the marketplace – getting it racked properly and getting into a position where the people who want it can have easy access to it.

What have you learned that might benefit small labels that are trying to find good distribution?

The biggest problem with distribution for a small label is, how do you get paid? That's one of the reasons why the deals that I've had [except Ryko] have been distributed through a major label. I'm able to do that because there's interest at those labels in the product, because it does sell, and it's a steady income for their custom pressing division. Whereas, another label might have difficulty making the same kind of a deal that I would make with a major.

The problem for an independent is, if he takes a chance and sends his product on a 90-day billing to a retailer, unless he's got a mega-hit coming in the door a few weeks later, that retailer ain't gonna pay him. So he's gonna wind up having to sue that retailer under the laws of the state in which the retailer lives. That means a lot of lawsuits in a lot of states all over the country if you're hoping for national distribution. If you press and ship through a major, you take advantage of the major's ability to get paid.

Would you advise somebody, if they had a small label, to try and get a pressing and distribution deal through a major?

I would say that that's the best way to get paid. If they can find another way to get paid, more power to 'em.

What about strings attached?

Not in my deal. Basically, I pay them to press it and ship it. They don't do any promotion. They don't do anything. All they do is press it, ship it and collect.

So you do the promotion, then?

We do very little promotion. Basically, it's just to get it into the store. We hardly ever put ads for records in any kind of trades or other publications. No TV. Basically, it's nothing.

But you're in a unique position, though. You're Frank Zappa. And because you've got a certain fan base built up, you're going to sell a lot of records by word of mouth.

One of the ways that I promote the record is by doing interviews. I find that I can get more coverage at a lower cost just by making myself available to talk on the telephone to somebody, instead of spending hundreds of thousands of dollars buying full-page ads in all these publications, with dubious results.

Besides, in an interview, you can give explanations about what's going on in a product, whereas in an ad, it's just the picture of the product and a small blurb. It's a maverick way of merchandising, but it works for me.

Do you see yourself ever cutting another deal with a major label?

The only deal that I could imagine being structured with a major label is if they wanted to purchase outright the key copyrights to the catalog.

Do you mean if, say, A&M called you up and said, "You know, we want to buy your catalog ..."

I'd negotiate with them for that.

But nothing else – you'd never allow yourself to be signed?

If a company bought the entire catalog, it would be stupid for me to stay independent if they have all the rest of my catalog. See, it would only be under the condition that I wouldn't go anyplace without my catalog. I like the idea of keeping it under the same roof.

Anything else you want to say about independent distribution, or the state of rock music today?

No. I think we both know the answer to that one.