Difference between revisions of "Jello Biafra"

m |

|||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | '''Jello Biafra''' (Eric Reed Boucher June 17, 1958) is an American punk rock singer, spoken word artist and record company executive who became famous in the 1980s as the leader of the [[San Francisco]] band Dead Kennedys. | |

| − | + | <blockquote>I don't think my generation has produced anybody the caliber of a Frank Zappa or [[Jim Morrison]] and part of the reason for that, per capita there weren't as many young people, it's post baby boom, also, it was the [[Ronald Reagan|Reagan]] era. The best and the brightest of the young minds, instead of going into music or resistance leadership, go into making money. Nobody seems to ask themselves 'Will this wealth, this distribution, suddenly seeing my name in crappy mall record stores, make me happy?' If the Dead Kennedys had gotten one tenth the size of Nirvana, I would've jumped off the Golden Gate bridge from pressure alone. Any creative, hard working person can't be bled of their talents forever and not be given any love in return — or they turn into either suicides or monsters.<ref>Jello Biafra, quoted from: [https://magazine.plazm.com/positive-cultural-terrorism-e6129cd86c7b#.qrnhvz370 Positive Cultural Terrorism], interview by Joshua Berger, Plazm #8, 1995</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | [[image:DKPoster.jpeg|right|thumb|200px|The offending insert]] | |

| + | In April 1986 Biafra, as head of the record company, was prosecuted for distributing harmful material to minors after including a poster by [[Wikipedia:H.R. Giger|H.R. Giger]] featuring penises and vulvae with the Dead Kennedys album [[wikipedia:Frankenchrist|Frankenchrist]]. The original painting had been show in art galleries in Europe and the USA. The album carried a sticker warning about the contents: | ||

| + | <blockquote>''The inside foldout<ref>Biafra had wanted the image to be part of the gatefold sleeve for the album but the other band members disagreed and so it was included as a separate insert.</ref> to this record cover is a work of art by H. R. Giger that some people may find shocking, repulsive, or offensive. Life can sometimes be that way.''</blockquote> | ||

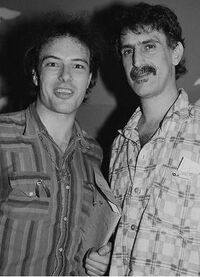

| + | [[File:Jello Biafra and Zappa.jpg|200px|thumb|right|Jello Biafra and Frank Zappa, 1985.]] | ||

| + | The album was released in October 1985, following the [[Parents Music Resource Center|PMRC hearings]] in August, and was seen as an opportunity to establish a legal precedent<ref>a spokesmen for the city attorney’s office said from the outset that they were not seeking jail terms. LA Times, August 28, 1987</ref> to ban what the PMRC considered 'Porn Rock'. As a small independent band and label they would not have sufficient funds to fight the case and the No More Censorship Defense Fund was established to raise money to defend the case. Zappa offered advice to Biafra during his legal battle. Biafra later recalled: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | Meeting Frank Zappa was one of the few silver linings to come out of the trial. He got a hold of me and the helpers of the No More Censorship Defense Fund rather than us having to find him. He gave me some very valuable advice very early on; something that anybody subjected to that kind of harassment should remember: You are the victim. You have to constantly frame yourself that way in the mass media so you don't get branded some kind of outlaw simply because of your beliefs and the way you express your art. The outlaws are the police. I got to visit Frank two or three more times at his house in Los Angeles and those were very special times. He showed me a hilarious Christian aerobics video. The women were in their skintight leotards doing jumping jacks. 'One-two, two-two, three-two, praise the Lord!' And of course the bustiest one was in a striped spandex suit dead front center of the screen! <ref>Jello Biafra, Punk Politics, Alternative Tentacles, 2004.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Ignoring advice to research the band and listen to the album prosecutor Michael Guarino pressed ahead with the case: | |

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

| + | “We were a couple of young prima donna prosecutors.”<ref>Washing Post, Jello Biafra: The Surreal Deal, May 4th 1997</ref>. | ||

| − | + | I remember looking at the piece of art and thinking, just on the basis of the insert, that we had a great case. It seemed to me that that is the kind of material that most adults wouldn't want to see distributed to kids.<ref>Michael Guarino: This American Life: I am curious Jello</ref> | |

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | The prosecution had been initiated after 15 year-old Tammy Schwarth's mother found the poster in the record sleeve and complained to California’s Attorney General’s office. She was surprised by the resulting legal case: | |

| + | <blockquote> “I thought I’d just have to complain and it would all be taken care of. . . . I didn’t realize it would all go to court and be a big to-do.”</br> | ||

| + | Her daughter commented on the image: "I thought it was gross--it wasn’t harmful.” <ref>[https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-08-21-mn-2358-story.html LA Times Aug. 21, 1987]</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | < | + | The defence lawyer [[wikipedia:Philip A. Schnayerson|Philip Schnayerson]] took on the case for free and argued that if artists were held liable for any material that might fall into the hands of minors, “that everyone will have to adhere to [that] standard and that adults would be reduced to reading and seeing things that would be acceptable only for minors.”<ref>"Measures of excess: The trial of Jello Biafra". The Sacramento Bee. August 9 1987</ref>. Schnayerson presented the jury with copies of the poster and played some songs from the album which helped establish the context. Professors and music critics were called as witnesses and the trial became an art and history lesson rather than a discourse about protecting children. |

| + | |||

| + | Guarino realised that he was being out manoeuvred, that the songs on the album promoted a positive anti-drug view, and he started to have doubts about his position: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>I did start to think that I was on, not the wrong side of the case so much, but more generally the wrong side of history. I just felt I was on the wrong side of history.</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The jury voted for an acquittal and the judge dismissed the case. The trial was a personal turning point for Guarino who would leave office and become dean of a small law school in northern California. Guarino's son became an avid Dead Kennedys fan and Biafra would eventually forgive him for his part in the prosecution.<ref>Thius American Life, [https://www.thisamericanlife.org/285/know-your-enemy/act-two-0 Know Your Enemy]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The band, increasingly disillusioned with the punk scene, disbanded at the end of 1987 to pursue solo projects before reforming in the early 2000s. Biafra recorded a spoken word album, [[wikipedia:High Priest of Harmful Matter: Tales from the Trial|High Priest of Harmful Matter: Tales from the Trial]] which included his view of the trial.<ref>Stream on [https://music.apple.com/album/tales-from-the-trial/275667263?i=275667305 Apple Music] and [https://open.spotify.com/track/1JV1YEcVfkh1WsaWoYMhWw?si=b7c98723102a4753 Spotify].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1997, Jello got to write a tribute to Zappa in the official [[Awards|Grammy Awards program book]]. | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Blood On The Canvas]] | *[[Blood On The Canvas]] | ||

| − | *[[Dead Kennedys]] | + | *[[Wikipedia:Dead Kennedys|Dead Kennedys]] |

| − | [[Category:Supporting Cast|Biafra | + | [[Category:Supporting Cast|Biafra]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Rock Artists|Biafra]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Singers|Biafra]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Celebrity Fans|Biafra]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Activists|Biafra]] |

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 13:52, 15 December 2021

Jello Biafra (Eric Reed Boucher June 17, 1958) is an American punk rock singer, spoken word artist and record company executive who became famous in the 1980s as the leader of the San Francisco band Dead Kennedys.

I don't think my generation has produced anybody the caliber of a Frank Zappa or Jim Morrison and part of the reason for that, per capita there weren't as many young people, it's post baby boom, also, it was the Reagan era. The best and the brightest of the young minds, instead of going into music or resistance leadership, go into making money. Nobody seems to ask themselves 'Will this wealth, this distribution, suddenly seeing my name in crappy mall record stores, make me happy?' If the Dead Kennedys had gotten one tenth the size of Nirvana, I would've jumped off the Golden Gate bridge from pressure alone. Any creative, hard working person can't be bled of their talents forever and not be given any love in return — or they turn into either suicides or monsters.[1]

In April 1986 Biafra, as head of the record company, was prosecuted for distributing harmful material to minors after including a poster by H.R. Giger featuring penises and vulvae with the Dead Kennedys album Frankenchrist. The original painting had been show in art galleries in Europe and the USA. The album carried a sticker warning about the contents:

The inside foldout[2] to this record cover is a work of art by H. R. Giger that some people may find shocking, repulsive, or offensive. Life can sometimes be that way.

The album was released in October 1985, following the PMRC hearings in August, and was seen as an opportunity to establish a legal precedent[3] to ban what the PMRC considered 'Porn Rock'. As a small independent band and label they would not have sufficient funds to fight the case and the No More Censorship Defense Fund was established to raise money to defend the case. Zappa offered advice to Biafra during his legal battle. Biafra later recalled:

Meeting Frank Zappa was one of the few silver linings to come out of the trial. He got a hold of me and the helpers of the No More Censorship Defense Fund rather than us having to find him. He gave me some very valuable advice very early on; something that anybody subjected to that kind of harassment should remember: You are the victim. You have to constantly frame yourself that way in the mass media so you don't get branded some kind of outlaw simply because of your beliefs and the way you express your art. The outlaws are the police. I got to visit Frank two or three more times at his house in Los Angeles and those were very special times. He showed me a hilarious Christian aerobics video. The women were in their skintight leotards doing jumping jacks. 'One-two, two-two, three-two, praise the Lord!' And of course the bustiest one was in a striped spandex suit dead front center of the screen! [4]

Ignoring advice to research the band and listen to the album prosecutor Michael Guarino pressed ahead with the case:

“We were a couple of young prima donna prosecutors.”[5].

I remember looking at the piece of art and thinking, just on the basis of the insert, that we had a great case. It seemed to me that that is the kind of material that most adults wouldn't want to see distributed to kids.[6]

The prosecution had been initiated after 15 year-old Tammy Schwarth's mother found the poster in the record sleeve and complained to California’s Attorney General’s office. She was surprised by the resulting legal case:

“I thought I’d just have to complain and it would all be taken care of. . . . I didn’t realize it would all go to court and be a big to-do.”

Her daughter commented on the image: "I thought it was gross--it wasn’t harmful.” [7]

The defence lawyer Philip Schnayerson took on the case for free and argued that if artists were held liable for any material that might fall into the hands of minors, “that everyone will have to adhere to [that] standard and that adults would be reduced to reading and seeing things that would be acceptable only for minors.”[8]. Schnayerson presented the jury with copies of the poster and played some songs from the album which helped establish the context. Professors and music critics were called as witnesses and the trial became an art and history lesson rather than a discourse about protecting children.

Guarino realised that he was being out manoeuvred, that the songs on the album promoted a positive anti-drug view, and he started to have doubts about his position:

I did start to think that I was on, not the wrong side of the case so much, but more generally the wrong side of history. I just felt I was on the wrong side of history.

The jury voted for an acquittal and the judge dismissed the case. The trial was a personal turning point for Guarino who would leave office and become dean of a small law school in northern California. Guarino's son became an avid Dead Kennedys fan and Biafra would eventually forgive him for his part in the prosecution.[9]

The band, increasingly disillusioned with the punk scene, disbanded at the end of 1987 to pursue solo projects before reforming in the early 2000s. Biafra recorded a spoken word album, High Priest of Harmful Matter: Tales from the Trial which included his view of the trial.[10]

In 1997, Jello got to write a tribute to Zappa in the official Grammy Awards program book.

Notes

- ↑ Jello Biafra, quoted from: Positive Cultural Terrorism, interview by Joshua Berger, Plazm #8, 1995

- ↑ Biafra had wanted the image to be part of the gatefold sleeve for the album but the other band members disagreed and so it was included as a separate insert.

- ↑ a spokesmen for the city attorney’s office said from the outset that they were not seeking jail terms. LA Times, August 28, 1987

- ↑ Jello Biafra, Punk Politics, Alternative Tentacles, 2004.

- ↑ Washing Post, Jello Biafra: The Surreal Deal, May 4th 1997

- ↑ Michael Guarino: This American Life: I am curious Jello

- ↑ LA Times Aug. 21, 1987

- ↑ "Measures of excess: The trial of Jello Biafra". The Sacramento Bee. August 9 1987

- ↑ Thius American Life, Know Your Enemy

- ↑ Stream on Apple Music and Spotify.