Difference between revisions of "Zappa Keeps Eye Now On Bottom Line"

Propellerkuh (talk | contribs) m |

Propellerkuh (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

'''Entrepreneurship: From his hilltop home in Laurel Canyon, the musician and his wife run several businesses.''' | '''Entrepreneurship: From his hilltop home in Laurel Canyon, the musician and his wife run several businesses.''' | ||

| − | Frank Zappa has long been known as a rock 'n' roll iconoclast, an outspoken, unconventional musician who earned the devotion of a moderate-sized following with such records as "Freak Out," "Weasels Ripped My Flesh" and "Sheik Yerbouti." But the former leader of the Mothers of Invention is also a shrewd businessman. "I don't have anything against making a profit," he said. | + | [[Frank Zappa]] has long been known as a rock 'n' roll iconoclast, an outspoken, unconventional musician who earned the devotion of a moderate-sized following with such records as "[[Freak Out!]]," "[[Weasels Ripped My Flesh]]" and "[[Sheik Yerbouti]]." But the former leader of the [[The Mothers|Mothers of Invention]] is also a shrewd businessman. "I don't have anything against making a profit," he said. |

| − | Zappa, who turns 49 today, always did part his hair differently than his more commercially successful contemporaries. But this year, while middle-aged rockers such as the Who, Paul McCartney and the Rolling Stones were reaffirming their popularity on high-profile concert tours, Zappa was smart enough to stay home. He hung up his road gear after he lost $400,000 on his self-financed 1988 tour. | + | Zappa, who turns 49 today, always did part his hair differently than his more commercially successful contemporaries. But this year, while middle-aged rockers such as the ''Who, Paul McCartney'' and the ''Rolling Stones'' were reaffirming their popularity on high-profile concert tours, Zappa was smart enough to stay home. He hung up his road gear after he lost $400,000 on his self-financed 1988 tour. |

"Everybody got paid but me," he said. Even though the four-month tour of the United States and Europe was 90% sold out, Zappa said the losses piled up because of high travel costs and salaries for the 12-piece band. There were 43 people in all, three buses and five trucks. "I had to pay the cost of all the airplane tickets, all the buses, all the food, all the per diems and salaries," Zappa said. | "Everybody got paid but me," he said. Even though the four-month tour of the United States and Europe was 90% sold out, Zappa said the losses piled up because of high travel costs and salaries for the 12-piece band. There were 43 people in all, three buses and five trucks. "I had to pay the cost of all the airplane tickets, all the buses, all the food, all the per diems and salaries," Zappa said. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

"That sort of dampens one's enthusiasm for going out there and doing it again," he said, adding that he's unwilling to accept financial backing from a corporate sponsor because it would mean hawking such products as beer or soft drinks. | "That sort of dampens one's enthusiasm for going out there and doing it again," he said, adding that he's unwilling to accept financial backing from a corporate sponsor because it would mean hawking such products as beer or soft drinks. | ||

| − | But Zappa is hardly struggling. Like any other businessman, he's worked at cutting his overhead and he looks for new business opportunities where he can find them, some as distant as the Soviet Union. From offices in North Hollywood and his hilltop Laurel Canyon home, Zappa and his wife | + | But Zappa is hardly struggling. Like any other businessman, he's worked at cutting his overhead and he looks for new business opportunities where he can find them, some as distant as the Soviet Union. From offices in North Hollywood and his hilltop Laurel Canyon home, Zappa and his wife for 22 years, [[Gail Zappa|Gail]], run several businesses: a record label, a mail-order company, a video company and a music publishing firm. All of the businesses are 100%-owned by Zappa and his wife and he says they are profitable, although he remains tight-lipped about sales and earnings. |

He owns the lucrative master tapes for many of his recordings, thanks to a lawsuit he filed against his former record company, Warner Bros. Records, and he slowly re-releases the old titles on compact discs. Much like an annuity, the money keeps coming from those re-releases. "My stuff sells year after year, and the income from those sales goes to me," Zappa said. | He owns the lucrative master tapes for many of his recordings, thanks to a lawsuit he filed against his former record company, Warner Bros. Records, and he slowly re-releases the old titles on compact discs. Much like an annuity, the money keeps coming from those re-releases. "My stuff sells year after year, and the income from those sales goes to me," Zappa said. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Since 1985, she has run the business end of things. "He's the artist and puts the product together. I handle all production aspects of it, the cover art and packaging. I make all the financial decisions." | Since 1985, she has run the business end of things. "He's the artist and puts the product together. I handle all production aspects of it, the cover art and packaging. I make all the financial decisions." | ||

| − | And lately, the man who produced "Valley Girl," (the 1982 hit he made with his daughter, Moon, who immortalized a series of Val-slang phrases, such as "Gag me with a spoon") has turned his sights to international trade and is brokering joint ventures in the Soviet Union, including a proposed deal to start a U.S.-Soviet business-oriented television show. | + | And lately, the man who produced "[[Valley Girl]]," (the 1982 hit he made with his daughter, [[Moon Zappa|Moon]], who immortalized a series of Val-slang phrases, such as "Gag me with a spoon") has turned his sights to international trade and is brokering joint ventures in the Soviet Union, including a proposed deal to start a U.S.-Soviet business-oriented television show. |

| − | In the fickle world of pop music, Frank Zappa never achieved superstar status, though he did have a few certifiable hits. According to Billboard magazine, Zappa's three biggest singles were "Don't Eat | + | In the fickle world of pop music, Frank Zappa never achieved superstar status, though he did have a few certifiable hits. According to Billboard magazine, Zappa's three biggest singles were "[[Don't Eat The Yellow Snow]]," which reached No. 4 on the charts in 1974, "[[Dancin' Fool]]," which hit No. 8 in 1979, and, with Moon, "[[Valley Girl]]," No. 12 in 1982. But the recordings were labeled by Billboard as novelty songs, meaning "it's like the Singing Chipmunks, more or less tongue in cheek," said Kim Whitburn, a spokeswoman for Billboard's record research unit. |

Zappa, however, concentrates on other numbers. He says artists can make lots more money by running their own record companies than by collecting royalties from someone else. | Zappa, however, concentrates on other numbers. He says artists can make lots more money by running their own record companies than by collecting royalties from someone else. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Warner Bros. executives declined to give figures on past sales of Zappa's albums, and they remain touchy about the lawsuit. "I'm not going to deal with any issue relating to Frank Zappa," said a source at the company, who asked that his name not be used. "If we say he sold 2 million records for us, he might come back and sue us for royalties." But the source did say Zappa's records consistently sold hundreds of thousands of units, which "wasn't huge, but it was substantial." | Warner Bros. executives declined to give figures on past sales of Zappa's albums, and they remain touchy about the lawsuit. "I'm not going to deal with any issue relating to Frank Zappa," said a source at the company, who asked that his name not be used. "If we say he sold 2 million records for us, he might come back and sue us for royalties." But the source did say Zappa's records consistently sold hundreds of thousands of units, which "wasn't huge, but it was substantial." | ||

| − | Zappa releases his new albums on his independent label, Barking Pumpkin Records, which he started in 1981. "We're taking all the risk a record company takes," he said. "We have to pay for our own recording, advertising, every other cost a record company would normally have. On the other hand, all the profit a record company would normally have is ours now." The records are distributed through a unit of Capitol Records. | + | Zappa releases his new albums on his independent label, [[Barking Pumpkin Records]], which he started in 1981. "We're taking all the risk a record company takes," he said. "We have to pay for our own recording, advertising, every other cost a record company would normally have. On the other hand, all the profit a record company would normally have is ours now." The records are distributed through a unit of Capitol Records. |

| − | In addition to the record company, Zappa also has a licensing deal with a Boston company, Rykodisc, which has distributed about two dozen of Zappa's old albums on CD during the past three years. Don Rose, president of Rykodisc, said that sales of a few of them have topped 100,000 units, a strong showing considering the recordings are up to 25 years old and that an album goes "gold" with sales of 500,000 units. | + | In addition to the record company, Zappa also has a licensing deal with a Boston company, [[Rykodisc]], which has distributed about two dozen of Zappa's old albums on CD during the past three years. Don Rose, president of Rykodisc, said that sales of a few of them have topped 100,000 units, a strong showing considering the recordings are up to 25 years old and that an album goes "gold" with sales of 500,000 units. |

| − | Though most of Zappa's income comes from the record business, a growing offshoot is his Barfko-Swill mail order company, which sells Zappa T-shirts, posters and postcards, as well as records and cassettes. He also runs a music publishing business, Munchkin Music; Honker Home Video, a company named after Zappa's nose and which has produced videos such as "The True Story | + | Though most of Zappa's income comes from the record business, a growing offshoot is his [[Barfko-Swill]] mail order company, which sells Zappa T-shirts, posters and postcards, as well as records and cassettes. He also runs a music publishing business, [[Munchkin Music]]; [[Honker Home Video]], a company named after Zappa's nose and which has produced videos such as "[[The True Story Of 200 Motels]]," based on Zappa's film "[[200 Motels (The Film)|200 Motels]];" and ''Joe's Garage,'' a rehearsal hall rental company. |

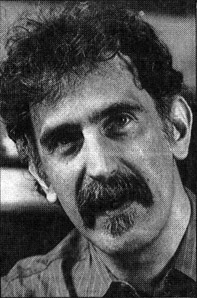

| + | [[Image:LAT_89-12-21-2.jpg|frame|In addition to a record business, Frank Zappa operates a mail order company, a music publishing firm and a home video company.]] | ||

And after four trips to the Soviet Union in recent years, Zappa has a variety of non-music deals he's trying to put together. He's already set up an agreement for a Chatsworth company to receive amber for jewelry-making from the Soviets, for which he received a 10% commission. | And after four trips to the Soviet Union in recent years, Zappa has a variety of non-music deals he's trying to put together. He's already set up an agreement for a Chatsworth company to receive amber for jewelry-making from the Soviets, for which he received a 10% commission. | ||

| − | He is also working on starting a satellite-linked television show that would feature Soviet and American business and legal experts exchanging ideas and information. He says cable channel Financial News Network is interested in the concept, and he has another working trip to the Soviet Union planned for January. Other joint U.S.-Soviet deals in the works include the possible manufacture of Ben & Jerry's ice cream in the Soviet Union. | + | He is also working on starting a satellite-linked television show that would feature Soviet and American business and legal experts exchanging ideas and information. He says cable channel Financial News Network is interested in the concept, and he has another working trip to the Soviet Union planned for January. Other joint U.S.-Soviet deals in the works include the possible manufacture of ''Ben & Jerry's'' ice cream in the Soviet Union. |

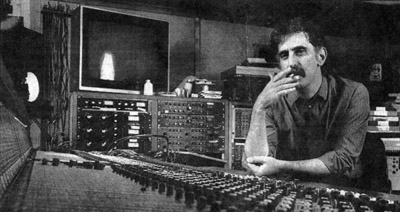

The Zappa home, where Frank and Gail live with three of their four children and where much of their business is run, is large but unpretentious. Wood-paneled rooms are dark and cluttered, and stacks of tapes line the walls. In one part of the house is Zappa's studio, where he started installing digital recording equipment in the early '80s, before the technology became a standard for recording. | The Zappa home, where Frank and Gail live with three of their four children and where much of their business is run, is large but unpretentious. Wood-paneled rooms are dark and cluttered, and stacks of tapes line the walls. In one part of the house is Zappa's studio, where he started installing digital recording equipment in the early '80s, before the technology became a standard for recording. | ||

| − | The studio also contains Zappa's beloved Synclavier, a computerized synthesizer that can be programmed to produce a vast array of sounds. | + | The studio also contains Zappa's beloved [[Synclavier]], a computerized synthesizer that can be programmed to produce a vast array of sounds. |

| − | + | Zappa was born in Baltimore, but his family moved around a lot because his father was a civilian employee of the military. The Zappas eventually settled in Lancaster, near [[Edwards Air Force Base]]. When he was about 12, Zappa became interested in drums because he liked "the sounds of things a person could beat on." | |

| − | Zappa was born in Baltimore, but his family moved around a lot because his father was a civilian employee of the military. The Zappas eventually settled in Lancaster, near Edwards Air Force Base. When he was about 12, Zappa became interested in drums because he liked "the sounds of things a person could beat on." | ||

| − | As a teen-ager, while other kids were spending their money on cars, Zappa was buying records by Igor Stravinsky and avant-garde musicians, such as Edgard Varèse. He formed his first band while still in high school. Zappa's first album was "Freak Out," which he recorded with the Mothers of Invention in 1965. Since then he has produced more than 50 albums, both with and without the Mothers. | + | As a teen-ager, while other kids were spending their money on cars, Zappa was buying records by [[Igor Stravinsky]] and avant-garde musicians, such as [[Edgard Varèse]]. He formed his first band while still in high school. Zappa's first album was "[[Freak Out!]]," which he recorded with the [[The Mothers|Mothers of Invention]] in 1965. Since then he has produced more than 50 albums, both with and without the Mothers. |

| − | A few years ago, Zappa went on a tour of another kind when he accepted some dates on the college lecture circuit. Zappa said the $15,000 per lecture he earned was practically all gravy | + | A few years ago, Zappa went on a tour of another kind when he accepted some dates on the college lecture circuit. Zappa said the $15,000 per lecture he earned was practically all gravy – which rattled him a little since he prefers touring with a band but can't justify the expense. The businessman explained: "The interesting thing about lecturing is I make more money sitting in a chair on a stage for 90 minutes than I do playing in a rock band because there's no overhead." |

[[Category:Articles about Zappa]] | [[Category:Articles about Zappa]] | ||

Revision as of 12:04, 15 February 2007

By Patrice Apodaca

Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1989

Entrepreneurship: From his hilltop home in Laurel Canyon, the musician and his wife run several businesses.

Frank Zappa has long been known as a rock 'n' roll iconoclast, an outspoken, unconventional musician who earned the devotion of a moderate-sized following with such records as "Freak Out!," "Weasels Ripped My Flesh" and "Sheik Yerbouti." But the former leader of the Mothers of Invention is also a shrewd businessman. "I don't have anything against making a profit," he said.

Zappa, who turns 49 today, always did part his hair differently than his more commercially successful contemporaries. But this year, while middle-aged rockers such as the Who, Paul McCartney and the Rolling Stones were reaffirming their popularity on high-profile concert tours, Zappa was smart enough to stay home. He hung up his road gear after he lost $400,000 on his self-financed 1988 tour.

"Everybody got paid but me," he said. Even though the four-month tour of the United States and Europe was 90% sold out, Zappa said the losses piled up because of high travel costs and salaries for the 12-piece band. There were 43 people in all, three buses and five trucks. "I had to pay the cost of all the airplane tickets, all the buses, all the food, all the per diems and salaries," Zappa said.

"That sort of dampens one's enthusiasm for going out there and doing it again," he said, adding that he's unwilling to accept financial backing from a corporate sponsor because it would mean hawking such products as beer or soft drinks.

But Zappa is hardly struggling. Like any other businessman, he's worked at cutting his overhead and he looks for new business opportunities where he can find them, some as distant as the Soviet Union. From offices in North Hollywood and his hilltop Laurel Canyon home, Zappa and his wife for 22 years, Gail, run several businesses: a record label, a mail-order company, a video company and a music publishing firm. All of the businesses are 100%-owned by Zappa and his wife and he says they are profitable, although he remains tight-lipped about sales and earnings.

He owns the lucrative master tapes for many of his recordings, thanks to a lawsuit he filed against his former record company, Warner Bros. Records, and he slowly re-releases the old titles on compact discs. Much like an annuity, the money keeps coming from those re-releases. "My stuff sells year after year, and the income from those sales goes to me," Zappa said.

It was a few years ago that Zappa and his wife decided to cut their overhead. They had employed managers, lawyers and accountants to run his music businesses. "After we started reading the contracts, we started to get smart and figured out maybe we could do it better," Gail Zappa said. "So I fired everyone and started over."

Since 1985, she has run the business end of things. "He's the artist and puts the product together. I handle all production aspects of it, the cover art and packaging. I make all the financial decisions." And lately, the man who produced "Valley Girl," (the 1982 hit he made with his daughter, Moon, who immortalized a series of Val-slang phrases, such as "Gag me with a spoon") has turned his sights to international trade and is brokering joint ventures in the Soviet Union, including a proposed deal to start a U.S.-Soviet business-oriented television show.

In the fickle world of pop music, Frank Zappa never achieved superstar status, though he did have a few certifiable hits. According to Billboard magazine, Zappa's three biggest singles were "Don't Eat The Yellow Snow," which reached No. 4 on the charts in 1974, "Dancin' Fool," which hit No. 8 in 1979, and, with Moon, "Valley Girl," No. 12 in 1982. But the recordings were labeled by Billboard as novelty songs, meaning "it's like the Singing Chipmunks, more or less tongue in cheek," said Kim Whitburn, a spokeswoman for Billboard's record research unit.

Zappa, however, concentrates on other numbers. He says artists can make lots more money by running their own record companies than by collecting royalties from someone else.

In 1983, Zappa sued Warner Bros. Records, alleging that Warner used questionable accounting methods to mislead him about royalties due from sales of his music, a practice he says is still common in the music business. Most artists don't take the time to closely scrutinize their contracts with record companies, Zappa said. But he wanted more control over the sales of his records.

When the suit was settled out of court, ownership of many of the masters reverted to him. Zappa said he spent about $1.6 million on the suit, but the steady sales of his old records are very lucrative. "I have albums that were released 10, 15, 20, 25 years ago that are selling substantial quantities in CD and cassette," he said.

Warner Bros. executives declined to give figures on past sales of Zappa's albums, and they remain touchy about the lawsuit. "I'm not going to deal with any issue relating to Frank Zappa," said a source at the company, who asked that his name not be used. "If we say he sold 2 million records for us, he might come back and sue us for royalties." But the source did say Zappa's records consistently sold hundreds of thousands of units, which "wasn't huge, but it was substantial."

Zappa releases his new albums on his independent label, Barking Pumpkin Records, which he started in 1981. "We're taking all the risk a record company takes," he said. "We have to pay for our own recording, advertising, every other cost a record company would normally have. On the other hand, all the profit a record company would normally have is ours now." The records are distributed through a unit of Capitol Records.

In addition to the record company, Zappa also has a licensing deal with a Boston company, Rykodisc, which has distributed about two dozen of Zappa's old albums on CD during the past three years. Don Rose, president of Rykodisc, said that sales of a few of them have topped 100,000 units, a strong showing considering the recordings are up to 25 years old and that an album goes "gold" with sales of 500,000 units.

Though most of Zappa's income comes from the record business, a growing offshoot is his Barfko-Swill mail order company, which sells Zappa T-shirts, posters and postcards, as well as records and cassettes. He also runs a music publishing business, Munchkin Music; Honker Home Video, a company named after Zappa's nose and which has produced videos such as "The True Story Of 200 Motels," based on Zappa's film "200 Motels;" and Joe's Garage, a rehearsal hall rental company.

And after four trips to the Soviet Union in recent years, Zappa has a variety of non-music deals he's trying to put together. He's already set up an agreement for a Chatsworth company to receive amber for jewelry-making from the Soviets, for which he received a 10% commission.

He is also working on starting a satellite-linked television show that would feature Soviet and American business and legal experts exchanging ideas and information. He says cable channel Financial News Network is interested in the concept, and he has another working trip to the Soviet Union planned for January. Other joint U.S.-Soviet deals in the works include the possible manufacture of Ben & Jerry's ice cream in the Soviet Union.

The Zappa home, where Frank and Gail live with three of their four children and where much of their business is run, is large but unpretentious. Wood-paneled rooms are dark and cluttered, and stacks of tapes line the walls. In one part of the house is Zappa's studio, where he started installing digital recording equipment in the early '80s, before the technology became a standard for recording. The studio also contains Zappa's beloved Synclavier, a computerized synthesizer that can be programmed to produce a vast array of sounds.

Zappa was born in Baltimore, but his family moved around a lot because his father was a civilian employee of the military. The Zappas eventually settled in Lancaster, near Edwards Air Force Base. When he was about 12, Zappa became interested in drums because he liked "the sounds of things a person could beat on."

As a teen-ager, while other kids were spending their money on cars, Zappa was buying records by Igor Stravinsky and avant-garde musicians, such as Edgard Varèse. He formed his first band while still in high school. Zappa's first album was "Freak Out!," which he recorded with the Mothers of Invention in 1965. Since then he has produced more than 50 albums, both with and without the Mothers.

A few years ago, Zappa went on a tour of another kind when he accepted some dates on the college lecture circuit. Zappa said the $15,000 per lecture he earned was practically all gravy – which rattled him a little since he prefers touring with a band but can't justify the expense. The businessman explained: "The interesting thing about lecturing is I make more money sitting in a chair on a stage for 90 minutes than I do playing in a rock band because there's no overhead."