Difference between revisions of "Zappa, City paper, 94-1"

Propellerkuh (talk | contribs) m |

m (link to Schorr page) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

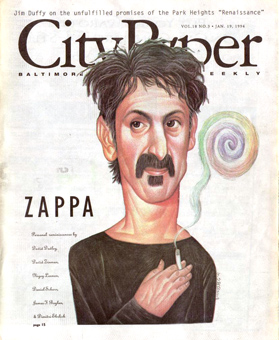

| − | Personal reminiscenses by David Dudley, David Zinman, [[Nigey Lennon]], Daniel Schorr, James F.Baylan, Dimitri Ehrlich<br> | + | Personal reminiscenses by David Dudley, David Zinman, [[Nigey Lennon]], [[Daniel Schorr]], James F.Baylan, Dimitri Ehrlich<br> |

City Paper, Baltimore weekly, No.3, 1994 January | City Paper, Baltimore weekly, No.3, 1994 January | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:CPB_94-03.jpg|frame|]] | [[Image:CPB_94-03.jpg|frame|]] | ||

Revision as of 06:14, 9 June 2008

Personal reminiscenses by David Dudley, David Zinman, Nigey Lennon, Daniel Schorr, James F.Baylan, Dimitri Ehrlich

City Paper, Baltimore weekly, No.3, 1994 January

David Dudley

Like the lion's share of interesting Baltimore-born artists, Frank Vincent Zappa, Jr., American composer (1940-93), blew town as soon as possible. The reason wasn't Tinytown's stifling postwar cultural or artistic climate. It was the climate, period. Young Frank had asthma, and as he writes in his 1989 autobiography, The Real Frank Zappa Book, "I was sick so often in Maryland, Mom and Dad wanted to move."

When Zappa died last month, a victim of prostate cancer at 52, you didn't hear much about the man's local roots in all the music paper obits – mainly because there wasn't much to say. Frank, Sr., taught history at Loyola for a while, then worked as a meteorologist at the Edgewood Arsenal, up in Harford County – that's where the Army stored mustard gas and other chemical weapons. In 1950, the Zappa clan moved to Lancaster, California, a dusty nowheresville near Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert. Frank was 10 years old. He considered returning to Baltimore as a teen, to attend the Peabody Conservatory, but instead he stayed in the desert and taught himself how to be a composer.

While he was here, Zappa lived in Army housing in Edgewood, moving into a rowhouse on Park Heights Avenue toward the end of his tenure in Maryland. Frank went fishing and crabbing in the bay with his dad, played with explosives and gas masks (always on hand in the Zappa household in case of a mustard-gas leak from the nearby Army base), ate peanut butter sandwiches, and generally had a fairly normal childhood existence. It was only when he got to California, started playing drums, and first heard French-born avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse that Frank Zappa started cranking out the music and cranking up the lifestyle that made him infamous.

It is for the music that Zappa should be remembered; he made a ton of it, some 60-something albums since Freak Out!, that mystifying double-album debut from the Mothers of Invention in 1966. The Mothers were an old r&b bar band called The Soul Giants until Zappa got ahold of them in '64 and taught them to play music such as the world had never known. It was nuts; a furious ear-bending mix of proto-acid rock, doo-wop, 50s r&b, cocktail jazz, surf music, and 20th-Century modern classical dissonance. Zappa's heroes were composers like Stravinsky and Webern and Varèse, and though he played a mean guitar, sang (soma), and came up with a handful of strange sophomoric "hits" (such novelty goofs as "Don't Eat The Yellow Snow," the disco parody "Dancin' Fool," the infamous "Valley Girl"), all that was secondary to his passion of composing demanding, uncompromising music – reams of it – that most people would never hear. "The decoration of fragments of time," he called his business.

Because there was no place on rock radio for such pieces as "Prelude To The Afternoon Of A Sexually Aroused Gas Mask" (an ode to young Frank's wild years in Edgewood from 1970's Weasels Ripped My Flesh album), Zappa was haunted for the rest of his career by his unshakable image as some freakish stoner weirdo who wrote crazy little songs. This, despite Zappa's own oddly Calvinist lifestyle (no drugs, no booze), virtuoso mastery of just about every conceivable musical idiom, dictatorial bandleading, and fierce work ethic. But the die was cast, and Zappa was forever doomed to the bitter fringe, which seemed only to fuel his rage to make more music.

"Americans hate music," he reasoned. There seemed no other explanation.

Except for hearing "Cosmik Debris" every once in a while on the radio (I guess it qualified as "classic rock"), Zappa didn't really make many inroads into my rock-and-roll world for a long time. I remember seeing him do "I'm The Slime" on Saturday Night Live when I was in junior high, and I saw 200 Motels, his incredibly strange 1972 pseudodocumentary film, on cable TV once. Neither made much of an impression, beyond general bafflement. In college, I knew a guy who cleared out late-night parties by playing Uncle Meat, that nutball 1969 Mothers album of squirrelly sound bites and scary noises. But when he came through town in 1988, on what turned out to be his last tour, I was curious and lucky enough to catch him.

Despite the crummy acoustics at the Towson State basketball arena (Frank would have probably called it "rancid"), the music was breathtaking. It was a 12-piece band, barreling through the most intricate arrangements of the wildest rock/jazz/classical mutations I had ever heard. I was just amazed. How the hell can he tell what s going on? How does the bass player keep up? How do they remember all those notes? It was like some fiendishly complex machine. Most of the crowd, of course, was too busy yelling for "Titties 'n Beer" in between pieces to pay much attention. Frank would scowl blackly and turn to face his band, commanding them to turn the virtuoso hysteria up another notch.

The show wrapped up with a medley of Beatles covers and, at the very bitter end, "Stairway To Heaven." It was a very reverent reading of the song, wickedly accurate, building and building with honest Zeppelinesque heaviness. And when it came time for the big guitar break at the end, the horn section suddenly came to life and played a staggering note-for-note duplicate of Jimmy Page's solo, in perfect unison. The horn section.

I was impressed, and not only because it was still, after all these years, a bitchin' solo. Philosophically, it worked on a number of levels. Zappa constantly railed against the stultifying sameness of the American musical state of mind, and no piece of music had been played to banality more relentlessly than "Stairway." And yet, when those saxophones started honking out the last riffs to the solo, the solo that every man, woman, and child in modern America had heard a billion times, the notes still had a life of their own. The music was everything.

Critics often griped that Zappa never took rock or jazz or anything else seriously, that his music was all just an elaborate put-on, a self-indulgent jab at an idiom and an audience that he felt was beneath him. True, Zappa never suffered fools, in music or politics or anywhere else. But no one who spent the time figuring out how to teach a brass section "Stairway to Heaven" could have done it with anything but genuine affection. It's just not worth it.

"No one writes that much music without taking it seriously," says Baltimore Symphony Orchestra conductor David Zinman, who conducted a Zappa piece, The Perfect Stranger, at the Meyerhoff just a week after Zappa's death. In life, Zappa the composer had a terrible time getting symphonies and chamber-music groups to take a stab at his serious orchestral works – partially because of his own eccentric demands, partially because he was convinced that the "serious" music establishment was interested only in hacking through ancient masterworks from dead composers, the Stairways to Heaven of the classical canon. And Zappa wasn't some art-rock dabbler in classical music; he wrote out his own scores, at enormous expense, and preferred to conduct them himself. He strictly specified instrument layout, demanded extra weeks of rehearsal time, and still was inevitably dissatisfied with the results.

"He didn't make it easy to perform his stuff," Zinman says. "Let's face it. His music is somewhat hard to put together."

The BSO seemed to do a yeoman job with The Perfect Stranger, however, running through its wacky polyrhythms and whirling unison xylophone bits in fine style. But when the final gong sounded and everyone clapped Zinman looked unsatisfied.

"Do you want to hear that again?" he asked the audience. The Meyerhoff crowd that night was an odd mix of well-dressed symphony seasoners and long-haired latter-day freaks wearing crusty old Mothers T-shirts; they all seemed mystified at the question. But Zinman returned to the podium and started the whole crazy thing over again, from the top.

"I'm glad I got a chance to try it again," he tells me later. When Zinman introduced the piece that night, he read a telling quote from Zappa's autobiography, with the author grumping about the world premiere of The Perfect Stranger in 1984, conducted by Pierre Boulez.

In the game of new music, everybody has to take a chance. The conductor takes a chance, the performers take a chance, and the audience takes a chance – but the guy who takes the biggest chance is the composer. The performers will probably not play his piece correctly ... and the audience won't like it because it doesn't "sound good." There's no such thing as a second chance in this situation – the audience only gets one chance to hear it because, even though the program says "World Premiere that usually means "Last Performance."

"So I thought," Zinman explains, "why not do it twice?" So he did.

Nigey Lennon

When I heard that Frank Zappa had succumbed to cancer on December 4, some two weeks shy of his fifty-third birthday, at first I found myself wondering if, like the old Mark Twain story, rumors of death weren't greatly exaggerated. The Frank Zappa I remember always stubbornly insisted on existing in his own space-time continuum, and it was difficult to imagine him meekly submitting to any other construct and shuffling off to oblivion.

My acquaintance with Zappa began in 1969, when I was a sophomore at Mira Costa High School in Manhattan Beach. I had made a home recording of some songs that I had written and sent it to Zappa's Bizarre Records. Like countless other teenage oddballs of the 60s, I identified fervently with Zappa's outré, in-your-face musical stance. The Mothers of Invention, his anarchistic band, had been my favorite group since I was 11, when their first album, Freak Out!, was released. I figured that because I was considered so weird by other kids at my school, I was probably some kind of genius, and that if anyone in the. music world would appreciate my talents, it would be Frank Zappa.

So imagine my reaction when I came home from school one afternoon to find a letter from Zappa himself, asking me to come in and talk to him at his office when he returned from a European tour. Somehow I had never really expected to meet my hero. All of a sudden, I didn't feel like such a genius. What would I say to him? How could 15-year-old me impress Frank Zappa?

On the date agreed upon, my boyfriend (who was also on the tape I'd sent to Zappa) and I showed up at the Bizarre Records office, which was located on the top floor of a nondescript Wilshire Boulevard skyscraper. (I had to wheedle a ride out of my father because I was too young to drive.) I was about ready to jump out of my skin with nervousness, but luckily I didn't have to suffer long: at precisely 3:30 p.m., Frank Zappa strode through the door, greeted the secretary, told her to hold his calls, and immediately herded us into a private suite. I don't think I ever felt so important in my life – or so fraudulent.

"Hiya," he said by way of introduction as we all sat down. His manner of speaking was clipped and to the point but strangely genial. He reached into the pocket of his brown tweed blazer and pulled out a piece of crumpled paper on which he had made what appeared to be copious notes about my tape. I couldn't help noticing that he was wearing a green feathered lady's hat. ("Junk-store item," he explained.) On any other six-foot-tall, black-mustachioed male, it would have looked aberrant, but it lent Zappa a jaunty, Renaissance-cavalier sort of air.

Then he proceeded to sing the first few lines of one of my songs! After that he could have knocked me over with his hat. "My father once told me the road to hell was paved with good intentions," he said with grave humor, fixing his dark eyes on me like a laser beam. "I like some of these songs, but nothing on this tape is ready to record yet." Reading from his notes, he gave us a song-by-song rundown on what he felt needed to be done to improve the demo. Although I was disappointed that he wasn't going to rush me into the studio immediately, I had to admit that his criticisms were intelligent and objective, especially considering the nature of the material. "When this stuff is ready, you'll be able to sell it anywhere, not just here," he said. "But I'd like to hear it again when you're finished," he added quickly, seeing my glum expression.

Business having been conducted, he put his feet up on the desk and started asking us questions – where did we live, where did we go to school, what kind of music did we like. He was remarkably avuncular and easy to talk to. In fact, I had never had such a good time talking to anyone before. I was truly sorry when he looked out the window – the neon Mutual of Omaha was just blinking over his shoulder – and gently let us know that he had other things to get to. More than two hours had passed in what I would have sworn was only 15 minutes. It was a big letdown when we finally shook his hand, bid him farewell, and got into the elevator to descend to the lobby and "reality" – whatever that was.

Although I had every intention of fixing up the demo and resubmitting it to Zappa, I never got around to it. I ran afoul of the school authorities and wound up being expelled in my junior year. My parents decided to send me to Arizona to take care of my grandmother, who was dying. In the process, I became involved in the rodeo world and put the idea of a professional music career on the back burner, although I kept writing songs whenever I happened to be sidelined with a fracture or a bad contusion. I still listened to Zappa's music as much as ever too, and when I arrived back in Los Angeles a couple of years later, I decided to try looking him up again.

After a local concert I went backstage and said hello to him. He immediately remembered me and asked how my music was going, and if I had a band. I told him what I'd been up to, and we chatted awhile. By this time he had disbanded his original Mothers of Invention and was trying out different personnel combinations, and knowing that I played the guitar and sang, he asked if I'd like to try out for his current road band. I had serious misgivings about being able to handle his high-tech arrangements, among other things, but I duly schlepped up to his home studio in Laurel Canyon, where I spent a horrendous afternoon getting inextricably tangled in suspended-fourth and raised-eleventh chords. I still don't know why, but less than two weeks later I found myself at a real live gig. It didn't work out, of course, but we became good friends anyway.

The more I got to know Zappa, the more opposite I began to realize we were: although he had been born in the United States, he was culturally a die-hard European (his father was a straight-off-the-boat Sicilian immigrant, and Frank had been brought up a strict Catholic), and he had an instinctive hatred of almost everything American, especially cowboys. I, on the other hand, was as western and barbaric as they come, and dang proud of it, and I'm afraid I took great relish in making a fetish out of the fact around Frank.

Being 14 years my senior, Zappa took his self-appointed role as my cultural mentor seriously, trying his best to civilize me by exposing me to "serious" (i.e., European) music – Stravinsky, Webern, Varèse, and whatnot. He never could get me to accept 12-tone or aleatory music as valid, but then, I could never convince him that Spade Cooley or Lefty Frizzell was anything but poot (his term for, er, waste). Those critics who took him to task for corrupting innocent youth with filthy lyrics would have been flabbergasted to see him sitting solemnly at the phonograph, playing me excerpts from his favorite composers and intently waving his cigarette like a pointer at critical junctures in the musical lecture.

Our differences showed up even more markedly in the gender department. Although he was unfailingly encouraging when it came to my music, I always got the impression that he was uncomfortable with me intellectually because I was a girl, The women around him tended to fall neatly into well-defined roles – his wife kept his domestic scene running like a well-oiled machine, and all the assorted groupies and camp followers who hung around the band served to make life on the road diverting. I, on the other hand, insisted on being his intellectual equal, and that confused him. Evidently there was nothing in his background to enable him to understand a loose cannon like me. The fact that our friendship survived some hairy disagreements was a testament to his endurance and my stubbornness.

I received a great deal of inspiration from Zappa, not all musical. You couldn't be around him and not experience the peculiar exhilaration that came from his total disregard of mundane reality; he created his own universe from the ground up by transforming things around him into exactly what he wanted them to be. I could imagine him as a gangly adolescent, shuffled around from school to school whenever his father's job as a government weapons tester required another move, and I could see how Frank, reading books on Zen Buddhism and listening to the expansive music of his idol Edgard Varèse, had developed his philosophy as a form of self-defense. As an adult, he had managed to turn it into both an art and a business – he was having the last laugh on a world that would gladly have banished him to the special hell reserved for eccentrics and dreamers. To me, that seemed like the most sublime sort of creativity.

Still, sometimes Zappa's private universe could get oppressive. He hated losing control, real or imagined, practically to the point of paranoia. Once, in New York during a tour, he rummaged through my carry-on flight bag and found my journal, which, being a record of my daily activities, contained various observations, pro and con, about what was going on around me. He flew into a rage and accused me, entirely without cause, of keeping notes so that I could sell an expose to Rolling Stone. I tried to explain that I had no such intention, but he wouldn't listen. Fed up with his shenanigans, I excused myself from that night's performance, which happened to be at Carnegie Hall. The next morning I heard that he had made a lengthy speech dedicating the show to me, as sort of a public apology. It was hard not to be fond of him, despite his eccentricities.

Our final rift was over the same sort of thing. I had an assignment from a national magazine to write about something – I don't even remember what, now – and I was supposed to survey various people about what they thought of whatever it was. Almost jokingly, I called Zappa and asked him if he'd like to participate in my survey. He was in a bad mood that night and accused me of being an opportunist and a turncoat, and that was the end of the staunchest, and strangest, friendship I probably ever had.

That was in 1975. More than once since then have I wished that I could sit again in his basement studio, sipping 60-weight espresso and listening to that flat, ironically affectionate voice discussing the science of acoustics, the significance of Rimsky-Korsakov's influence on Stravinsky, or the idiocy of American voters. There was a lot I didn't understand about my friendship with Frank Zappa, but now that I know it's over for good, I realize how lucky I was to have known him, and I'm truly sorry I never told him so.

Daniel Schorr

The following was taken from the transcript of the December 6, 1993, National Public Radio broadcast of "All Things Considered." During the broadcast, NPR news analyst Daniel Schorr spoke of his friendship with Zappa.

It was the unlikeliest of friendships, between the avant-garde of music and the old guard of journalism, and it started in the unlikeliest of ways. Out of the blue, Frank Zappa called me from Los Angeles in August 1986. Luckily, my teenage daughter was on hand to tell me who he was.

He wanted to come to Washington to talk to me about doing a fate-night television show together. Mouths dropped around NPR when he came to my office. His plan was for a program featuring his band and including a segment to be called "Night School." It would be a way of telling the news to rock fans turned off on current events. Responding to questions from him and his musicians, I would tell what was really going on in Washington, a sort of continuing Watergate watch.

The show never got off the ground, but our friendship did. I came to know that behind the angry, sometimes profane words he spoke about cultural mediocrity and government conspiracies was a true musical genius who cared a lot about young people. During a concert tour, he had me come onstage to join him in a voter-registration appeal.

He wanted to foster a peaceful youth revolution to take over a government he saw as corrupt. Another manifestation of his urge to rock the establishment was his feud with Tipper Gore over dirty song lyrics. But his diatribes didn't spare the youth culture that hearkened to him like Pied Piper.

He denounced hippies as phony and drugs as stupid. He also mocked himself and his own success. But his self-deprecation was deceptive. He talked about fooling around with music, not letting you know how deeply he was into Bach, Mozart, and the classic tradition. He talked over my head about harmonic climates, and he traveled to Czechoslovakia, became a close friend of Václav Havel, and studied folk songs of Eastern Europe, writing serious music on their themes. He was also contrary. Talk about his success, and he would say he was a failure. Talk about his popularity, and he said he was lonely. Maybe he was. Maybe the world around him was too crass, too mediocre, too homogenized. So he cursed it with dirty words, and went back to his music synthesizer, searching for new musical meanings. And ways of serving kids. His own, and the world's.

James Finney Baylan

Like a lot of people, I suppose my adolescence could be divided in its distinct each defined by a certain friend, fashion, and music. The Zappa Phase came immediately after my hard labor as a Deadhead, which came on the heels of various obsessions with Jethro Tull, the Stones, and God knows what else. I confess, in 1974, to having attended an Alice Cooper concert at which Alice cut off his own head with a giant guillotine and later drank his own blood. At least he said it was his own blood.

Zappa's music, however, was not just a phase. Sure, the pornographic hilariousness of it was a dependable way to offend one's parents when necessary, but the amazing thing about Zappa's music was not its raw weirdness. Zappa's music was serious in a way that, to my 14-year-old ears, opened up a new way of listening to and interacting with music.

I remember listening to a short piece on the album Uncle Meat (1969) – to my ears still Zappa's finest. At a certain point, after some snorkel sounds and the laughter of an infant, the music suddenly gave way to what seemed like a cacophony of harpsichords. I still recall the shock and wonder I felt when I realized that the sounds consisted entirely of the main theme of the album, played in 13 different keys, at dozens of different tempos. I think at that moment I first realized that the beauty of music can be found in its construction as well as its sound.

After a few years of this, of course, my friends and I got to be serious snobs: longhairs. You couldn't talk while a Zappa album was playing – you had to sit there and be quiet and listen to the damn thing. On some occasions we turned out the lights because you didn't want to be distracted by looking at stuff when you should be listening. There were times when we got up and started a piece over in the middle because we couldn't wait for it to be over so we could listen to it again.

So I owe Frank Zappa for opening up to my Watergate-generation, late-Nixon adolescence a way of learning how to interact with art, for teaching me that you can be an intellectual without being boring, that you can be a serious artist and still have a sense of humor, and that you can produce material most popular critics will hate and still be able to make your way-with pride and hilarity-as a creative person in America.

I would have liked to be able to thank Frank Zappa for all that.

I almost got my chance once. In 1988 or so – on what would be Zappa's last tour, I believe – I saw him play the Warner Theater, in D.C.

After the show I went to an almost-closed Chinese restaurant in D.C.'s Chinatown with my wife and my best friend from high school, Kenny, the guy at whose house I had spent so many hours in the early 70s listening to Frank.

About halfway through dinner my wife's eyes turned to saucers. There at the table next to us, sitting down with his family, was Zappa himself, looking a little tired.

Kenny and I sat there, wondering whether we should make ourselves known to Zappa. And let him know that we had been enjoying his music for at least 15 years now, that we had him to thank in large measure for our present professions – mine as a novelist and professor, Kenny's as a computer genius. Kenny, in fact, thought of the ideal salutation: going to the men's room and putting our underwear into one of those white cardboard Chinese takeout containers, and quietly presenting him with the same.

But we relented, being somewhat shy, and also, I suppose, feeling that the man should be allowed to eat his dinner with his family in peace without being accosted with fans bearing yet more underwear. So instead, as we left the restaurant, we paused for a moment by Zappa's table. Still wondering what we could say, still wondering if anything could be said.

At that very moment Zappa put his face down into his dish and scooped up the largest glob of cold sesame noodles I have ever seen a human eat in one bite. We stood there, wanting to say something, as the great man slurped his noodles. My wife wisely took us by the arms and directed us toward the door.

As we walked out into the cold night, my friend Kenny turned to me and said, quietly, what I want to say now, one last time.

"Thanks, Frank."

Dimitri Ehrlich

A few months before he died, I called frank Zappa for a brief phone interview. The subject was Z, a group formed by his two sons, Dweezil and Ahmet, and their debut album, Shampoo Horn. The record was released on Zappa's own Barking Pumpkin label, and the music bears his distinct imprint: complex, adventurous – at times difficult listening – but never prosaic or obvious. If the playing isn't quite as visionary as the best work of their father, the songs on Shampoo Horn find the young Zappa brothers fusing a kind of hard-rock fusion that's probably more relevant to their own time than the consistently avant-garde work of the elder Zappa ever was.

At the time this interview took place, the prostate cancer that took his life on December 4, 1993, was beginning to keep Zappa bedridden occasionally and exhausted much of the time. But he consented to speak with me, perhaps out of fatherly love, perhaps because he remained until his death an amazingly hard-working professional. We spoke only for about a quarter of an hour, and he was curt and somewhat grumpy throughout. His words came slowly and carefully, in a gravelly voice that reflected not only the considerable physical effort speaking had become for him, but also the deep level of thoughtfulness that he always required of himself.

How does it feel to have your sons carrying on your tradition?

I'm excited about it because they're doing such a good job of it, and I think the performance level of the group is amazingly high. And it's not just the quality of their recording, but their live performance too is quite astounding when you see it.

What about the songwriting?

My favorite thing that Dweezil does is his instrumental writing. The lyrics have gradually improved over the two or three previous albums, and I think he's got some pretty funny songs on this. Partly because Ahmet is contributing some lyric material. I think some of the lyrics fall into the "Venutian Vaudeville" category. And the accompaniment tracks I would describe as very technically oriented speed metal.

Except that the changes in time signature are outside the bounds of most speed-metal.

Yeah, most heavy metal is 4/4. But not them.

As a father, it must be a dream come true to have your children working together so harmoniously, no?

I think they work pretty well together, and obviously I'm a proud dad when it comes to watching them perform. I went to see them at the Club Lingerie [in L.A.]. It was fantastic.

What's the chemistry like in their working relationship?

Well, basically, Ahmet has a relationship with the audience, and Dweezil is a bandleader. Ahmet's a real frontman and jumps around and does all kinds of strange things onstage, which gives Dweezil the opportunity to concentrate on the guitar a little bit more, which is fine for his personality 'cause he's quite a bit more shy than Ahmet is.

From a strictly technical point of view, it's not easy to be influenced by your music, due to its sheer complexity. What do you feel that your sons have gotten from you musically?

Well, the first thing that seems to be a similarity between what I do and what Dweezil does is a complete and utter dedication to music as an art form rather than as a form of recreation. He really wants to get in and develop musical ideas. And considering that he's not formally educated, he's managed to do a lot of very interesting things from a technical standpoint. Where I might know what the technical names of those things are, he doesn't, but he can still do them. And from a rhythmic angle, a lot of what he does is similar to what I do – and in many instances exceeds it.

In what ways?

Just the types of rhythms that their band will play; these are things that I probably wouldn't try to get my band to play, mainly because I was using more musicians in my band, and it's harder to get a larger number of people to play all those kinds of tricky rhythms in a synchronized way. But his five-piece group manages to pull it off, and some of it is pretty astounding.

What kind of work schedule do Dweezil and Ahmet keep?

They work eight hours a day, five days a week.

Is that a work habit that you instilled in them?

No, that's Dweezil's idea.

What do you want people to know about what Z are doing?

Well, the first thing I want them to know is I think it's really excellent and it's worth a listen, even though it's not in 4/4.

What did you think of the title Shampoo Horn?

Well, in a way it doesn't apply now, since Ahmet is completely bald. He shaved his head, so the album cover is the last chance to see Ahmet with hair on his head.